Yet another of my great feminist and spiritual teachers has died. Rosemary Radford Ruether, ecofeminist Catholic theologian, died on May 21st. Her work challenged my thinking and gave me new understandings and perspectives. She was a prolific writer, authoring hundreds of articles and 36 books, and was the quintessential scholar and historian of world religions and ecofeminist theologies. A scholar of the scholastics, she examined three strains of Western thought: 1) the Hebraic tradition; 2) Platonic-Greek; and 3) Pauline-Augustinian in all their complexities to develop an understanding of the nature of Western thought and its implications for the domination of women, nature, and colonized others. As she described her own approach, she drew out the contradictions and complexities in these theologies, careful “to see both negative and positive aspects . . . and to be skeptical of exclusivist views on either side” (Women and Redemption, 222). Her thought and writing were ever-expanding, and always striving “to see the dominant system of patriarchy, including its racism, classism, and colonialism, in critical perspective,” and to put herself “in places where in solidarity with its victims, I can see it from its underside” (Women and Redemption, 222). To this end, she brought together the ecofeminist theologies of women from around the globe, particularly the global south.[i] Her thought also grew to include critiques of militarism and corporate globalization. Needless to say, I cannot begin to encompass all of her contributions here. So, I will focus on the ways her thought has most deeply influenced and inspired my own.

I first encountered Ruether’s thought in the piece excerpted from her Sexism and God-Talk in Plaskow and Christ’s Weaving the Visions, in which she not only challenged the assumption of the male divine, but also argued that “male monotheism reinforces the social hierarchy of patriarchal rule, . . . [and] “begins to split reality into a dualism of transcendent Spirit (mind, ego) and inferior and dependent physical nature . . . whereas the male is seen essentially as the image of the male transcendent ego of God, woman is seen as the image of the lower material nature. . . .Gender becomes a primary symbol for the dualism of transcendence and immanence, spirit and matter” ( 251-252). In a few sentences, she laid out the basic premise of the ecofeminist theological critique of Western thought.

In this piece, Ruether provided evidence of the many ways that the Bible itself challenges male monotheism, showing how Yahwism appropriates the goddess Asherah of its conquered peoples, incorporating female images of God -- God as mother and as woman in travail, particularly when describing the compassionate and loving aspects of the divine, as in the Hebrew word of compassion and mercy, rechem, meaning womb. She also explored the wisdom tradition of the logos of Sophia, the paired images for God as male and female in the parables, and notions of Yahweh as the god of liberation from bondage.

Two points Ruether made in this piece had a particularly profound impact on my understanding. The first is her discussion of the proscription of idolatry. This proscription precludes any representation of the divine – pictorial or verbal – no images of God as the old man with the white beard and no verbal depictions of God as male or as Father. What a profound and liberating recognition that was for me.

The other was Ruether’s critique of Christianity’s reliance on the divine as parental. This model, she claimed, depicts God as a “neurotic parent who doesn’t want us to grow up,” in which the gravest sin against God is to become morally autonomous and responsible, creating “spiritual infantilism as a virtue” (160). Her discussion of God as parent would always facilitate discussions with students about their issues with imaging God as a parent, when their experiences with their own parents were negative, dominating, or abusive.

Finally, in this piece she laid out the foundation of the ecofeminist theology that would underscore all of her subsequent work: “Feminist theology must fundamentally reject this dualism of nature and spirit” (161). In the original work, Sexism and God-Talk, Ruether developed her ecofeminist theology, questioning the hierarchy of human over nonhuman nature as well as other structures of social domination, declaring the God/ess as the “primal Matrix, the ground of being . . . Spirit and matter are not dichotomized but are the inside and outside of the same thing” (Sexism, 85).

In the postscript to Sexism and God-Talk, Ruether offered a powerful analysis of the ways this dualism, in which “woman/body/nature” are regarded as inferior to “man/spirit/culture,” contributes to the subjugation of women. The first of the three levels of subjugation of women -- “the subjugation of her womb, of access to her body” -- seems particularly pertinent given the increasing curtailing of women’s reproductive freedom in this country. Inscribed in ancient laws that continue to influence Western consciousness and law is the idea that women’s bodies and their offspring belong first to their fathers and then their husbands. She cited Catholic church doctrine that birth is shameful, and that only through a second birth of baptism, administered by male priests, is “the filth of mother’s birth remedied” (260). But the following in particular still seems the perspective of many of the new anti-choice legislation arising in state after state: “Woman is taught that the worst of sins, the worst of crimes, is to deflect the male seed from its intended course in her womb. This is more sinful than rape, (emphasis mine), for the rape of a woman does not interfere with the purposes of the seed, while contraception wastes the precious seed and defeats its high purposes. . . . She must obediently accept the effects of these holy male acts upon her body, must not seek to control their effects, must not become a conscious decision maker about the destiny of her own body” (261). It is this deep-seated, long-held belief that I believe is the true intention, even if subconscious, of those who would seek to restrict women’s reproductive autonomy.

The second level of women’s subjugation, exploited labor, has modified a bit since Ruether first wrote this forty years ago, but it is still the case that “black women, brown women, immigrant women toil silently in the background” (262), and for most women, the double day of paid employment and unpaid labor of tending children and households continues.

The third level, the rape of the earth and its peoples, has if anything increased. As she wrote, “The labor of dominated bodies, dominated peoples. . . provides the tools through which the earth is despoiled and left desolate. Through the raped bodies the earth is raped. Those who enjoy the goods distance themselves from the destruction” (263). The destruction of the Amazon rainforest to supply beef to distant consumers; the mining of the earth of African nations to supply gold, diamonds, and platinum to bejewel the bodies of the wealthy and leisured; the routing of oil pipelines through Native American reservations and ceded territories and the drilling of tar sands oil causing death and destruction to the indigenous populations and the earth so that the developed world can continue to burn fossil fuels to drive and fly and live in heated comfort – these are just some of the ways this subjugation plays out every day.

Yet, forty years ago, Ruether was hopeful for a metanoia – a true change of heart and consciousness – in which we would reject this dualism and instead live in right relation with each other and the earth. Nevertheless, writing just a few years later, she would forewarn of the reality we are living today, urging that “we must effect this metanoia quickly . . . By 2030 CE it may be too late, or at least too late to save much of the life-capacity of the biosphere that could be saved now. Instead, we will find ourselves operating on the other side of global catastrophes, with much narrower options” (Gaia, 86).

In Ruether’s later work, she would incorporate her understandings of the new physics into her rejection of dualism, describing the matrix as “the dancing energy. . . .of the interconnections of the whole universe” (Gaia, 248). She also proposed her key concept of “biophilic mutuality” – that all life energies have a desire to be in relationship with each other, and that the deep ontological structures that underlie this propensity are what she considered to be God. “God is not a ‘being’ removed from creation; . . . God is the source of being that underlies creation and grounds its nature and future potential for continual transformative renewal in biophilic mutuality” (Women and Redemption, 223.)

She believed in the deep interdependency and kinship of all beings, envisioning the good society of “communities of celebration and resistance,” in which true metanoia is practiced, replacing “the death system” with a “joy in the goodness of life” where we become good listeners of each other’s stories, and “take the time to sit under trees, look at water, and at the sky . . . and get back in touch with the living earth” (Gaia, 268-270).

Ruether’s thoughts on our ephemeral existence seem an appropriate benediction on her extraordinary life and work: “Then, like bread tossed on the water, we can be confident that our creative work will be nourishing to the community of life, even as we relinquish our small self back into the great Self. Our final gesture, as we surrender ourself in the Matrix of life, then can become a prayer of ultimate trust: ‘Mother, into your hands I commend my spirit. Use me as you will in your infinite creativity’” (Gaia, 253).

Notes

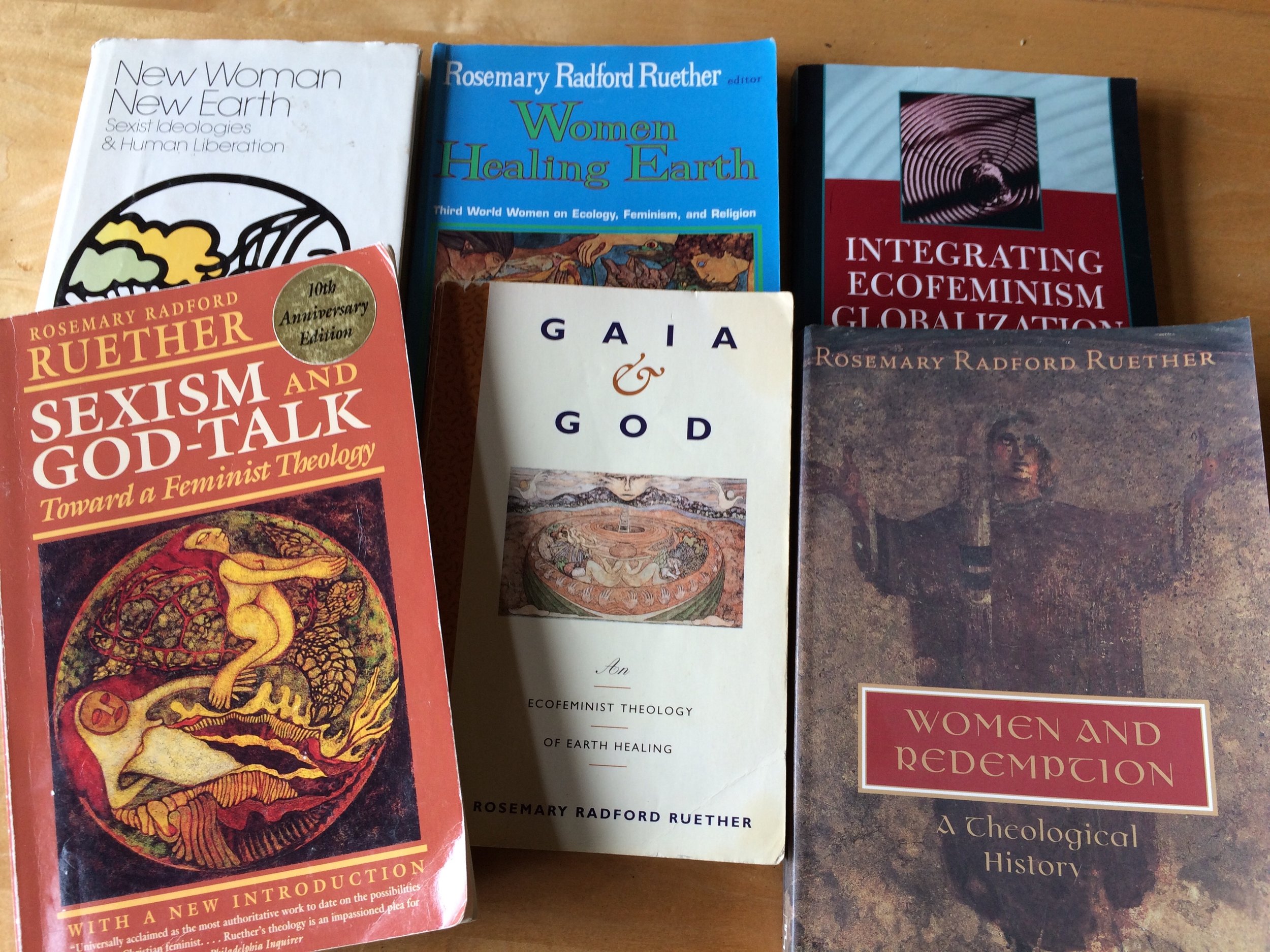

Ruether, Rosemary Radford. Gaia & God: An Ecofeminist Theology of Earth Healing. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1992.

______. Integrating Ecofeminism, Globalization, and World Religions. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Pub., Inc., 2005.

______. “Sexism and God-Language,” in Plaskow, Judith and Carol P. Christ, eds. Weaving the Visions: New Patterns in Feminist Spirituality. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1989: 151-162.

______. Sexism and God-Talk: Toward a Feminist Theology. 10th Anniversary ed. Boston: Beacon Press, 1983, 1993.

______, ed. Women Healing Earth: Third World Women on Ecology, Feminism, and Religion. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1996.

______. Women and Redemption: A Theological History. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress Press, 1998.

[i] See particularly Women Healing Earth: Third World Women on Ecology, Feminism, and Religion; Integrating Ecofeminism, Globalization, and World Religions; and Women and Redemption: A Theological History.