On May 29th, 1851, a striking, very tall, African American woman rose to speak at the Women’s Rights Convention being held in Akron, Ohio. There Sojourner Truth gave her famous “Ain’t I a Woman Speech.”

Originally named Isabella, and known as “Bell,” Truth was born into slavery in 1797, the second youngest of James (“Bomefree” – Dutch for “tree”) and Elizabeth (“Mau-mau Bett”) who were enslaved by a wealthy Dutch man, Johannes Hardenbergh, Jr., who had a large estate in Ulster County, New York, which was inherited by his son, Charles, when Truth was just an infant. Upon the death of Charles, at the young age of nine, she was sold at auction to John Nealy, where she “suffered ‘terribly-terribly’ with the cold”[i] and beatings. In her own words, “He whipped her till the flesh was deeply lacerated, and the blood streamed from her wounds – and the scars remain to the present day.”[ii] She prayed for deliverance, and soon after was sold to a fisherman and tavern owner, Martinus Schriver, where she led “a wild, out-of-door kind of life,” carrying fish, hoeing corn, foraging roots and herbs for beer. Only a year later she was sold again to John J. Dumont, where she lived out the remainder of her enslavement until her emancipation by the State of New York in 1828. She described her life there as “a long series of trials” which she did not detail “from motives of delicacy, . . . or because the relation of them might inflict undeserved pain on some now living”[iii] whom she regarded with esteem. Knowing the conditions of enslaved women, we can deduce what those trials entailed. Despite her affections for a man on a neighboring estate, who was beaten to death for visiting her when she was sick, she was forced to marry a much older man, Thomas, also enslaved by Dumont, with whom she bore five children. Because Dumont reneged on his promise to free her, she walked away with her infant daughter in 1827 and was taken in by the Van Wegener family where she lived for the next year.

Eventually she moved to New York City, where she joined the Zion Church and met up with a brother and sister she had never known, and for a short time joined a short-lived religious sect which took all of the money she had saved over the years. As a result, she became sure that the Golden Rule of “Do unto others as you would have others do unto you,” had not been practiced on her. Developing a revulsion toward money, she felt called by the spirit to leave New York City, to travel east and to lecture and preach. In 1843, she took up the name of “Sojourner Truth,” from then on made her way in the world as an itinerant preacher in the camp revival meetings sweeping that part of the country at the time. She drew her religious beliefs and inspiration from her mother’s assurance that there was “a God, who hears and sees you,” who “lives in the sky.”[iv] Illiterate, she memorized the entire Bible by asking children to read it to her.

Gaining a reputation as an eloquent and passionate orator, her travels would lead to her meeting abolitionists William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass, who enlisted her in the anti-slavery movement, where she also met many involved in the women’s rights movement. In 1850, she dictated her Narrative to Olive Gilbert. Living on the proceeds from its sale, she moved to the Quaker city of Salem, Ohio, the headquarters of the Anti-Slavery Bugle, and it was from there that she traveled to the Women’s Rights Convention held forty miles away in Akron in 1851, and gave her famous speech.

The speech recorded by Frances Gage several years later, with the “ain’t I a woman” refrain, is the one with which most are familiar, though the actual speech as transcribed at the time by Marius Robinson, while similar in content, does not contain the refrain, but rather she simply states that she is “a woman’s rights” woman.[v] It is unlikely that she spoke in the southern dialect Gage used in her transcription, since she grew up knowing only Dutch, eventually learning English as spoken in New York, and probably spoke with a Dutch accent. Much of the content in the Gage version was fabricated – such as the statement that she bore thirteen children, when she only had five children, though she did cry out in a mother’s grief when she learned that her only son, Peter, had been illegally sold south to Alabama.[vi]

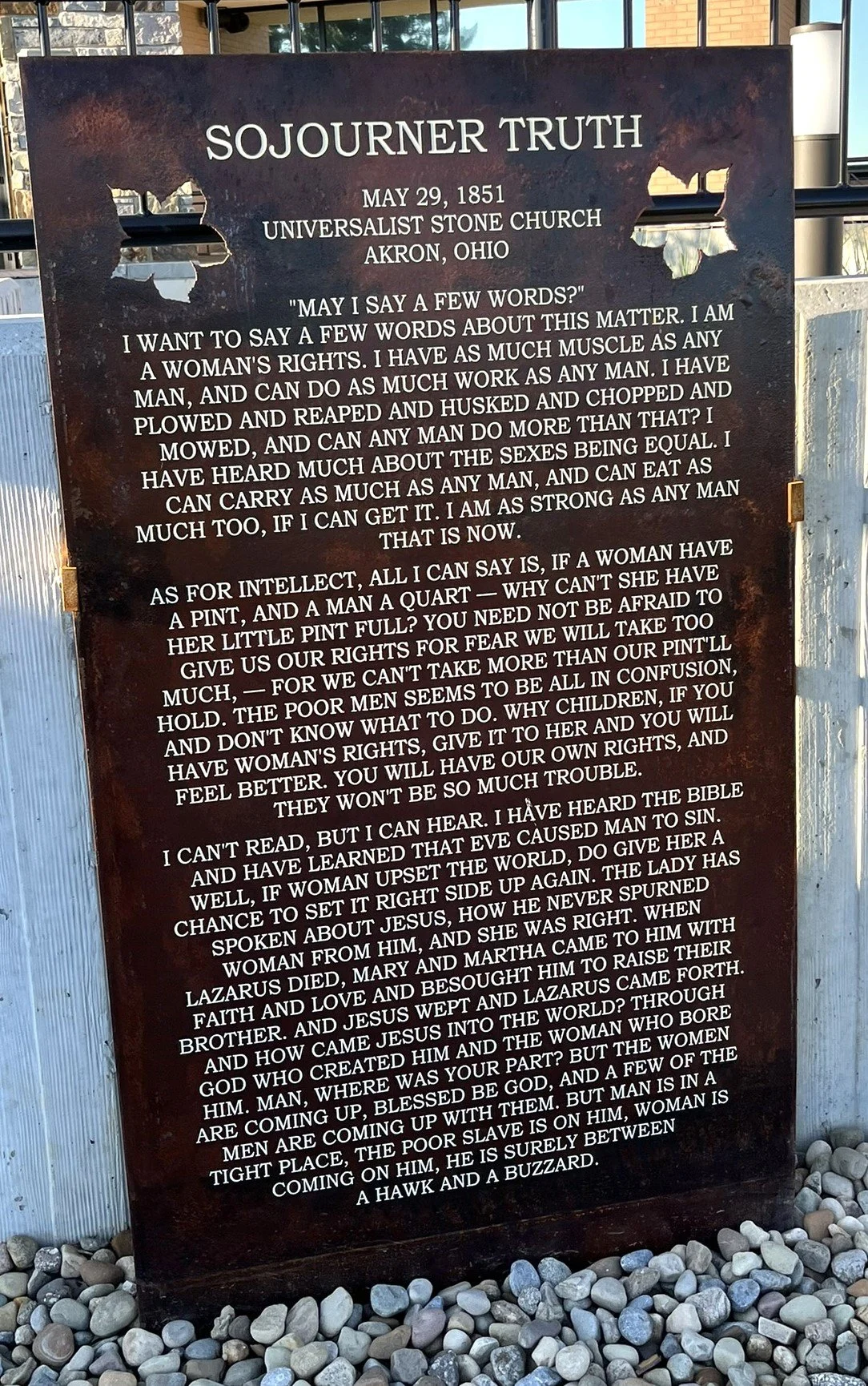

In the more accurate version of Truth’s speech, she claims women’s equality with men by referencing her own story – how she had done “men’s” work all her life and was equally as strong, remarking “I have as much muscle as any man, and can do as much work as any man. I have plowed and reaped and husked and chopped and mowed, and can any man do more than that? . . . I can carry as much as any man. . . I am as strong as any man that is now.” Indeed, her former master said of her, “’that wench is better to me than a man—for she will do a good family’s washing in the night, and be ready in the morning to go into the field, where she will do as much at raking and binding as my best hands.’”[vii] She didn’t claim the same intellect as a man, perhaps because she herself was illiterate, but she didn’t think that should disqualify women from having the same rights as men, and certainly, she argued, women should be able freely to exercise the intellect they did have. Finally, as a religious and faithful woman, referencing Eve and how women have been subordinated to men because of “Eve’s sin,” she argued, “if woman upset the world, do give her a chance to set it right side up again.” She spoke of how Jesus welcomed women, never rejected them, and perhaps most famously notes how Jesus was born of God and a woman, and asks, “Man, where is your part?” I can imagine the few women in the mostly male crowed laughing and cheering at that remark! She closed by saying “the women are coming up blessed be God.” She went on to deliver speeches throughout Ohio and Indiana on a speaking tour for women’s suffrage.

Though she never actually used the line, “Ain’t I a woman?”, this was the essential question of her speech, for certainly Black enslaved women had been doing the work of men and been treated as enslaved Black men and worse for centuries in this country. But as a Black woman, she had not been regarded as a woman, but rather as something else, something lesser. Her remarks raised the consciousness of her listeners, and advocated equally for racial and gender equality.

During the Civil War, she helped recruit Black soldiers for the Union Army, and afterward was honored with an invitation to the White House. She became involved in the Freedman’s Bureau and helped those formerly enslaved find employment and start new lives. She continued to work for women’s suffrage all of her life, and split with Frederick Douglass when he put Black male suffrage ahead of female suffrage. As she said in a later speech, “There is a great stir about colored men getting their rights, but not a word about colored women; and if colored men get their rights, and not colored women theirs, you see the colored men will be masters over the women, and it will be just as bad as it was before. So I am for keeping things going while things are stirring.”[viii] She eventually settled in Battle Creek, Michigan, where she lived out the remaining years of her life.

As a native of Akron, I had long been aware of the lack of any tribute to Truth in Akron, and for years from a distance had been hoping to connect with others who were interested in taking up such a project with me. At long last, I was able to find someone in the Women’s Studies department at the University of Akron who connected me with the Sojourner Truth Project, a project that had been begun decades ago, but had languished after its leader, Faye Hersh Dambrot died. It was picked up again in 2019. Since then, the excitement has built as funds have been raised and a plaza dedicated to Truth has been built under the leadership of Towanda Mullins, who garnered the support of the Akron City Council’s Park and Recreation Committee and then the full Council. And on the 173rd anniversary of Truth’s speech, the evening of May 29th, 2024, a six-foot bronze statue of Truth, created by local artist Woodrow Nash was unveiled. It was a great celebration with guest speakers, including one of Truth’s descendants, music, a ribbon cutting, and of course, the unveiling.

The Sojourner Truth Legacy Plaza in which the statue stands is a stunning tribute to her life, with a path winding throughout marking the milestones of Truth’s life.

Four pillars rise up from the plaza in remembrance of the four pillars of the Old Stone Universalist Church where Truth gave her speech, each one dedicated to the four pillars of her life and beliefs – activism, identity, power, and faith. Placards on the pillars display famous quotes from Truth’s life.

The landscape architect who designed the plaza, Dion Harris, remarked that he “wanted to make every aspect mean something,”[ix] and he certainly succeeded in doing that. Being in that space, surrounded by her life and words and visage was a very powerful experience for me. As Harris said of her, “Truth was one of those people who took her truth, took how she lived and was able to tell everyone about it and make something positive happen in the end if she wasn’t alive to see some of it.”[x] I have long admired her, and am so grateful to all those who made this possible, and am thrilled finally to see her life and legacy honored in the place where she first gave that famous speech.

Sources

Schreck, Isabella. “Plaza dedication to honor legacy of Sojourner Truth,” Akron Beacon Journal, May 26, 2024, 1A and 5A

Truth, Sojourner. “Keeping Things Going While Things are Stirring.” In Kolmar, Wendy K. & Frances Bartkowski, eds. Feminist Theory: A Reader. 4th Ed. New York: McGraw Hill, 2013. 91-92.

Truth, Sojourner. Narrative of Sojourner Truth. Ed. and with an Introduction by Margaret Washington. New York: Vintage, 1993.

[i] Truth, Narrative, 15.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Ibid., 18.

[iv] Ibid., 7.

[v] For a comparison of the two versions of Truth’s speech, see Compare the Speeches — The Sojourner Truth Project.

[vi] She worked with lawyers and the grand jury in New York to secure Peter’s return and eventual emancipation, and was the first Black woman successfully to sue a white man.

[vii] Truth, Narrative, 20.

[viii] Truth, “Keep Things Going,” 92.

[ix] Harris, quoted in Shreck.

[x] Ibid.