The full Beaver Moon last week was truly spectacular. The nights were clear and cold, the moon so big and bright. As I drove north out of the Twin Cities, it rose directly ahead of me, huge and rosy orange. It kept me company all the way home. When I crested the top of Thompson Hill, it lit up the city below, its beams sparkling across the great expanse of water beyond, welcoming me home. Bentleyville had nothing on that moonlight.[i]

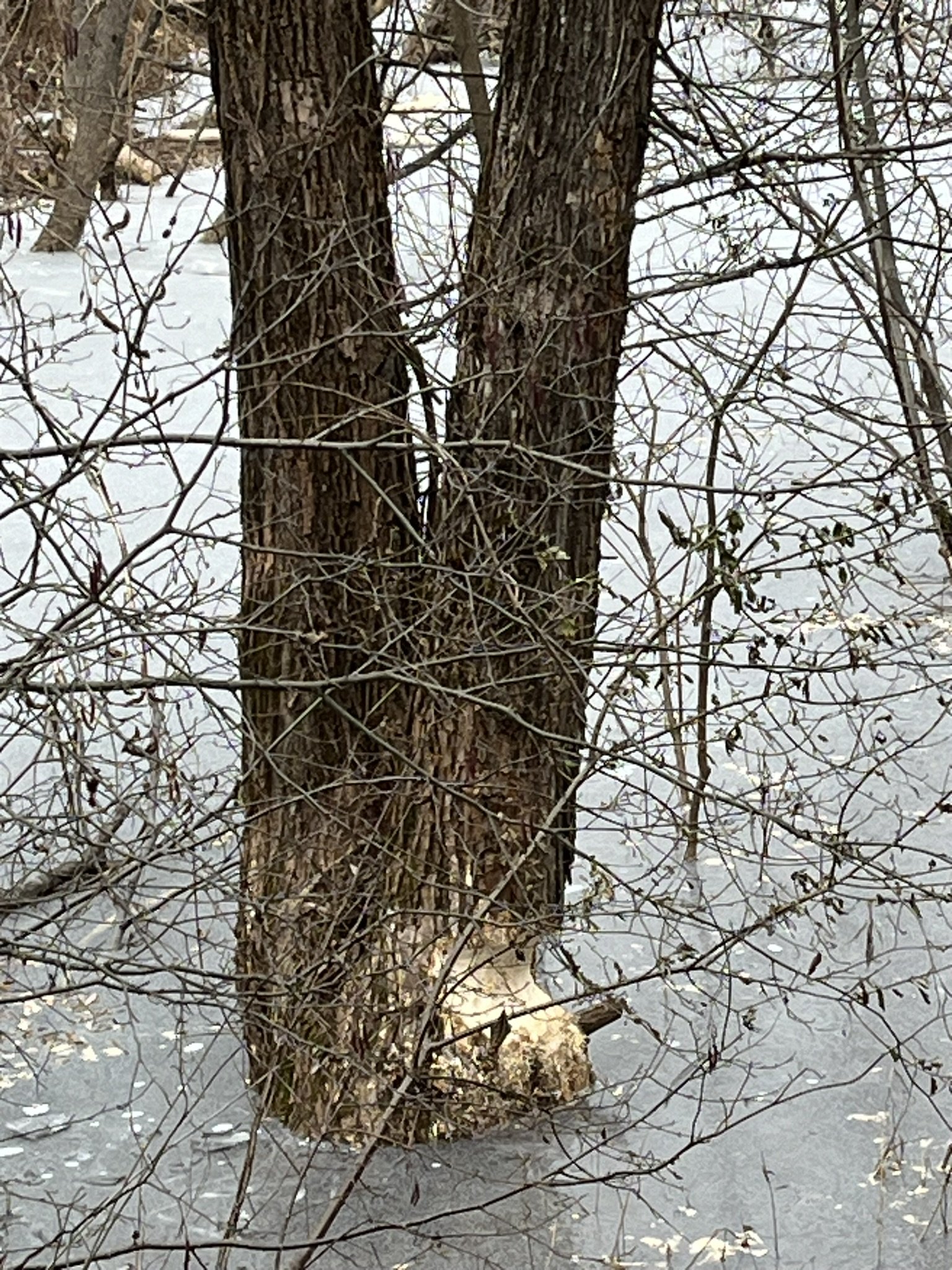

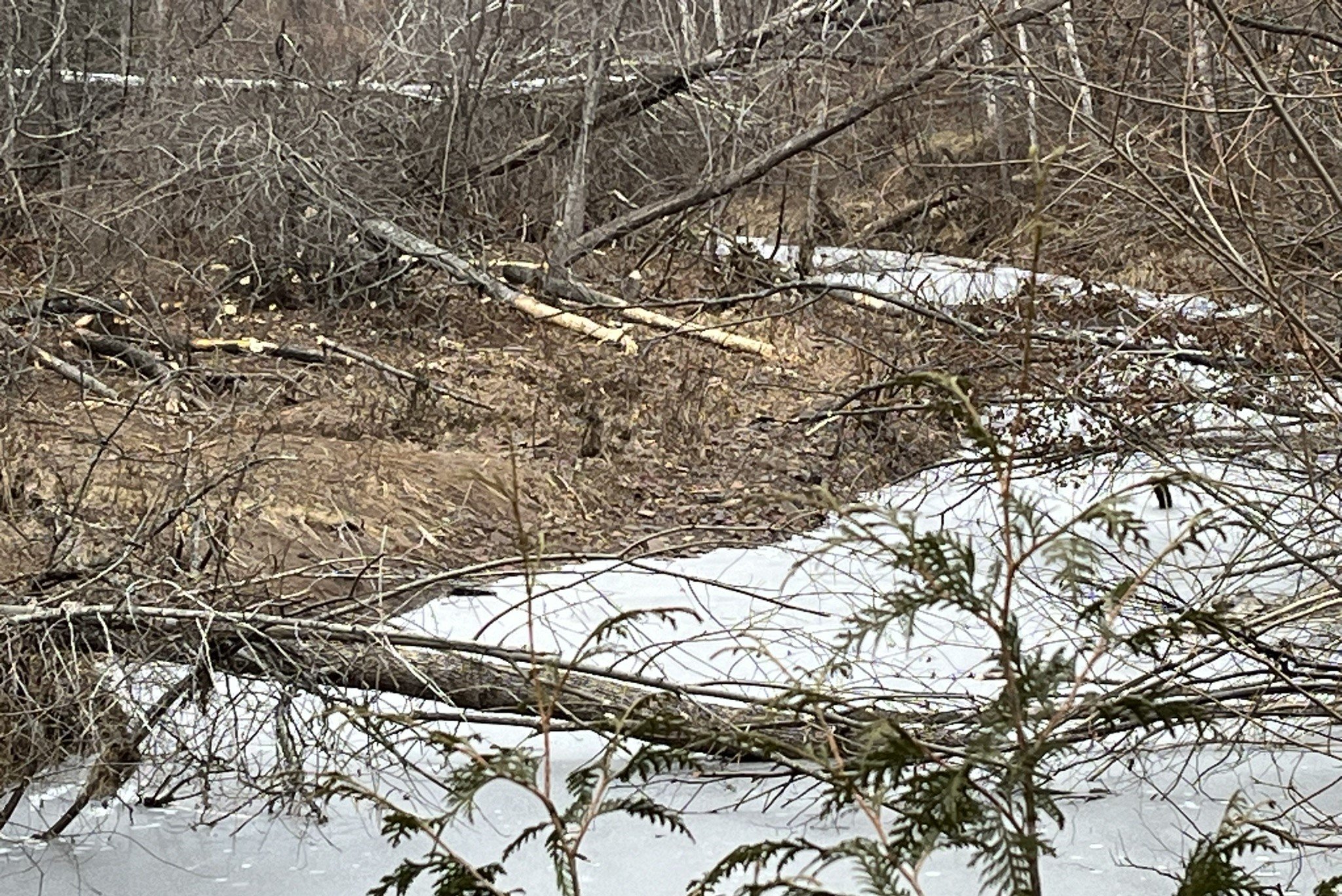

I didn’t need to Google “Beaver Moon” to know the reason behind the name, (though Googling did confirm my guess.) The beavers have been very busy this time of year as they prepare their dams and huts for the long winter ahead. Along the Amity, where I walk nearly every day, they’ve moved upstream and have been cutting down hundreds of trees, building a new and bigger dam than the series of dams that were destroyed either by the DNR or by the huge rain event a few months ago. Their lumbering capacity is truly impressive, toppling trees a foot or more in diameter. And it’s not just the Amity. I’ve seen evidence of their activity in every stream I’ve walked across the length of the city — from the Amity in the east to the West Branch of Merrit Creek in Piedmont Heights to Kingsbury Creek and the St. Louis estuary in the far west.

Undoubtedly regarded as destructive by human residents, either the DNR or the city park department, not sure which, keeps attempting to keep them at bay, removing their dams, trapping them and moving them out of the city. Years ago, they moved a large family of beaver upstream from the section of the Amity, where they had been living for several years, to what was then a relatively unpopulated part of the Amity. There they lived happily for a few decades, creating a huge beaver pond that provided a home for waterfowl in the summer and a wonderful skating rink for people of all ages in the winter. However, after the bike trail was built along the edge of the pond and beavers continually cut down trees that blocked the bikers, the dam was destroyed and the beavers trapped and moved.

It was a few months later that my dog, Ben, ran squealing and yelping out of the Amity where he’d been romping with another dog, blood streaming down his rear leg. A friend and I tried to staunch the bleeding with no luck. Our only alternative was to get him to the vet as quickly as possible. By the time we’d made it more than the mile back to the car and to the vet, Ben had lost so much blood that his tongue and gums were white. The vet wasn’t sure he’d make it through surgery. At the time, the vet asked me if there were any beavers in the stream, and I told him I hadn’t seen any beavers in that section of the Amity for years. Fortunately, Ben made it through. No vital nerves, muscles, or blood vessels had been cut. The vet said it was a clean cut -- looked to be metal of some kind, but there was another deep puncture wound as well, farther up his leg, that looked curved and somewhat triangular.

My husband and I went in search of what we suspected was an old metal trap or an old saw, but when we got to that section of the stream what we found instead was a large mama beaver[ii] swimming directly toward us, warning us that we were intruding. Apparently some of the beavers upstream hadn’t been trapped, and had made it downstream, where they must have been starting to make a new home.

I read a lot about beavers after that. I discovered that the vet was right about the clean cut being metallic. Beaver teeth are filled with iron, making them bright orange and incredibly sharp, which is how they are able to fell such huge trees. The incisors are curved and somewhat triangular, forming the deep puncture wound Ben suffered. While not particularly aggressive, beavers will attack animals, human and otherwise, when feeling threatened. Just a dog’s (or person’s) presence in the water at the wrong time and place makes it vulnerable to attack. Beavers tend to latch on, and can kill by dragging the threatening intruder under the water and drowning them, or if they lacerate the femoral artery, their victim will quickly bleed out, as happened to a man trying to photograph one.

Beaver hut

Beavers mate for life, every year birthing litters of one to six kits who live together with them until they are about three, at which time they move out to find mates of their own. They are the largest of North American rodents, and like all rodents, their teeth never stop growing so they need to chew to keep their teeth at a manageable size. And chew they do. They cut down trees incessantly, especially in the fall, creating and maintaining the dams which provide the depth of water needed to secure an underwater entrance to their huts, protecting them from the many predators who find their meat quite a delicacy. According to environmental engineer Alice Outwater, sometimes it seems they also build dams “just for fun” (23). Herbivores, beavers also stockpile cut trees for winter food, feasting on the inner bark all winter long.

While I’ve been upset with developers who have cut down large swaths of local forests to build condos and big box stores, I can’t extend the same umbrage to the beavers, despite the fact that they have cut down hundreds of trees by my beloved creek. Beavers are considered “keystone species,” critical to the survival of most of the other species in their ecosystem. As a result of their dam building, beavers create wetlands. Being ecotones – places of transition between two diverse communities – wetlands are rich in life – frogs, herons, migrating ducks, muskrats, moose, deer, and plants ranging from large fir trees to cattails to the tiniest of plankton – algae, fungi, bacteria. The phytoplankton feed on impurities in the water, while the slowed water allows sediment carried by streams to settle. The wetlands clean the water to crystal clear, while also building layers of rich topsoil. They also act like a sponge, soaking up water during storms and releasing it slowly during drier times, allowing it to seep into aquifers below rather than run off into the sea.

It’s estimated that prior to European contact two hundred million beavers lived throughout North America, from the Arctic to Mexico (with the exception of the swamps of Louisiana and Florida where they were killed off by alligators), creating vast wetlands and feeding the great aquifers. But after colonization, Europeans’ insatiable desire for the treasured beaver fur, first to warm them under beaver robes, but later simply for the fashionable beaver hats, led to the decimation of the beaver population from east to west across the continent. By the 1840s, the North American beaver was nearly extinct. Today beavers number only seven to twelve million, found mostly around the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River valley. Their demise has brought a decline in the amount and quality of water, the erosion of topsoil, massive damage from flooding, increased droughts, and decreasing numbers of the many species of plants and animals that depends on wetlands to survive. Vast areas of the US that were once water-rich are now arid as a result.

In England and Scotland, where beavers were hunted to extinction a century or two before Europeans arrived in the Americas, beavers mysteriously have reappeared and, to the chagrin of some farmers, are now a “protected species,” with an eye to reversing the severe droughts that have plagued Great Britain of late. However, in the US, beavers are not considered an endangered species. Considered by many to be a “nuisance animal,” beavers continue to be trapped and killed in the US, including nearly 25,000 by the US Department of Agriculture’s Wildlife Service in the last year alone. However, with increased awareness of the many benefits beavers bring, more and more efforts have been made to restore and protect them.

Rather than bemoaning the fact that the beavers seem to be destroying every tree in sight along the Amity, I remind myself that they are hard at work creating wetlands teeming with life, cleaning the water, preventing floods, droughts, and wildfires, and welcome them. They will be quiet now for many months to come, keeping cozy warm together in their huts and growing fat on their rich stores of wood pulp, but they’ll be back again, busily cutting down trees next fall, under the Beaver Moon.

Sources

Beaver Attacks and Nearly Kills Massachusetts Man | Field & Stream (fieldandstream.com)

Beaver Teeth: Everything You Need To Know - A-Z Animals (a-z-animals.com)

Keystone Species (nationalgeographic.org)

Man tries to take photo of beaver; it kills him (usatoday.com)

Outwater, Alice. 1996. Water: A Natural History. New York: Basic Books.

'They're aggressive': Edmonton beaver attacks prompt warning from Alberta trapper | CBC News

[i] For those not from Duluth, Bentleyville is a huge holiday light display with over five million lights in the shapes of Christmas trees, snowflakes, Santas, reindeer, and huge arched walkways, drawing thousands of people every year.

[ii] Female beavers tend to be larger than males, weighing about sixty pounds.