“. . . I know, yes, there is renewal, /because this is what the seeds ask of us/ with their own songs/ when we listen to their small bundle of creation,/ of a future rising from the ground . . .” - Linda Hogan

The first seed catalogs started arriving in the mail even before the turn of the new year. In an annual ritual of hope, in the depths of winter we turn our thoughts and dreams to growing things – seeds of heirloom tomatoes, cucumbers, squash, carrots, and beans that will feed us and grace our tables in the summer and fall, and colorful marigolds, nasturtiums, and zinnias that will delight all summer long with their beauty. Is this the invincible summer of which Camus wrote?[i]

Even as a young child, I yearned to plant seeds, and asked for a small patch of earth somewhere where I could grow a bit of lettuce and maybe some carrots. I sensed my mother found this a bit curious, since we had no vegetable garden. Nor did any of our friends and neighbors. I just knew I wanted to dig in the dirt, sow seeds, and tend a garden. My mom let me have a small area of dirt in a neglected corner by the garage, and for several years I planted, and weeded, and watered, and watched the lettuce grow. (I didn’t particularly like lettuce at that point in my life, but I loved growing it!)

It is a bit of a miracle – the growing of seeds. I’m in awe of “. . . the magic,” as Jane Goodall describes it, “the life force within a seed that is so powerful that tiny roots, in order to reach the water, can work their way through rocks, and the tiny shoot, in order to reach the sun, can find a way through crevices in a brick wall” (Seeds of Hope, 118). I especially marvel at the tiniest of seeds – lettuce, kale, carrots, tomatoes -- those barely-the-size-of-a-pinhead seeds that hold all the information to become large and leafy greens, long sturdy root vegetables, and round, luscious, juicy, voluptuous fruits (or are tomatoes vegetables?) that feed us year-round -- sliced fresh and made into sauces, salsas, juices, stews, and soups.

Just add dirt, water, and warmth and the unfolding begins. It is always such a delight when the first shoots pop up through the dirt. Yay, it worked!

At the beginning of the pandemic, fearing that we would soon be without fresh vegetables, I began growing lettuce indoors, (Yes, I like lettuce now.) as well as the tomato, cucumber, and squash plants I’d usually buy from a nursery. What’s more, as gardener Meg Cowden notes, seed-starting indoors, “provides a wellspring of hope as frigid winter days turn to weeks and months. . . .it is far more joyful to measure the growth of our seedlings than the accumulation of snow on garden beds” (161).

The seed is a miracle in and of itself -- an undeveloped embryo of the mature plant, containing the DNA passed on for millennia, surrounded by all the food and nutrition it needs to give it a good start, with a protective coating to insure its safety until the conditions are right for it to germinate.[ii] Each mature plant creates dozens, sometimes hundreds of offspring seeds, insuring the continuance of the species for generations to come. Plus, they share their bounty with us. Of the 250,000-300,000 varieties of plant species, 10,000-50,000 are edible, and 7000 are farmed and used for food.[iii]

Humans have been saving and planting seeds for millennia, but in recent decades, this long tradition has nearly come to a halt. Following World War II, chemical companies, needing to find new markets for the chemicals they had been developing for use during the war, found an outlet for their chemical fertilizers, herbicides, and pesticides in agriculture. Touted as “The Green Revolution” that would save millions from starvation, industrialized agriculture relied on hybridized high-yield seeds that required massive amounts of fertilizer and irrigation to grow. The emphasis on monocrops for high yields of cash crops led to reduction of seed diversity and to reliance on more and more chemicals as these farming techniques rapidly depleted the soil of its inherent nutritional value. Add to this the 1980 landmark US Supreme Court decision in Diamond v. Chakrabarty.[iv] Ananda Mohan Chakrabarty, along with GE, had genetically engineered pseudomonas bacteria and sought to secure a patent for it, in violation of US law excluding plants and animals from patents. However, the Court held that life is patentable as long as there is sufficient human intervention to alter naturally occurring lifeforms. The decision created the precedent for seeds becoming “owned” under intellectual property rights. Soon after, the US Patent Office decision in ex parte Hibberd in 1985[v] secured the right to patent genetically modified (GM) plants based on the decision in the Chakrabarty case, clearing the way for thousands of genetically engineered seeds to be patented.[vi] Indigenous farmers, who had been saving seeds for millennia, now were forced instead to buy these patented seeds under GATT[vii] and as conditions to secure loans under International Monetary Fund and World Bank “structural adjustment programs” (SAPs). Patent protection, argues ecofeminist and seed advocate Vandana Shiva, “transforms farmers into suppliers of free raw material, displaces them as competitors, and makes them totally dependent on industrial supplies for vital inputs such as seed” (Biopiracy, 54).

One of the many miracles of seeds is that over thousands of years they have evolved to thrive under different environmental conditions, resulting in copious varieties of seeds -- thousands of varieties of rice in India, potatoes in the Andes, sweet potatoes in Papua New , maize in Mexico, wheat in China, apples in the United States.[viii] However, the patenting of seeds and their forced use as dictated by First World multinational corporations, as well as the fact that four multinational corporations control around 60 percent of the world’s seed sales[ix] has led to the demise of seed diversity. Of the ten thousand varieties of wheat in China, only a thousand remain. Similarly, Mexico has lost 80% of its maize varieties, and the thousands of rice varieties once grown in the Philippines have diminished by 98% to the two varieties introduced by the Green Revolution.[x] Between 1903 and 1983, the United States lost 93% of its seed diversity.[xi]

Locally, the patenting of seeds has threatened multiple varieties of wild rice – manoomin -- found in Minnesota lakes. The University of Minnesota began developing its own version of domesticated “wild” rice in the early 1900s, and in 2000, U of M plant geneticist, Ron Phillips, mapped the wild rice genome, making it available for public use.[xii] Most of what is now sold as “wild” rice is actually paddy-harvested patented “wild” rice grown in California.

Additionally, the patenting of seeds has made the thousands-year-old practice of seed saving illegal, as is the sharing of seeds from farmer to farmer. The most notorious case is that of Canadian farmer Percy Schmeiser, who regularly saved and shared his seed, but whose canola crops were contaminated with Roundup Ready canola pollen blown into his fields from neighboring corporate farms. When Monsanto trespassed onto his fields, took samples, and found Roundup Ready canola plants mixed in with Schmeiser’s own canola plants, they sued him for violation of patents. Ultimately, the Canadian Supreme Court ruled in favor of Monsanto, but also ruled that Schmeiser owed Monsanto nothing.

Closer to home, the legality of seed sharing became an issue when in 2013 our local library decided to start a seed library. The project, initially proposed by Kelly Erb, an intern with the Institute for a Sustainable Future[xiii], was begun with great hopes that patrons could check out seeds for their home gardens, with the understanding that they would save a portion of their seeds and return these to the library for next year’s use. Project leaders hoped this would preserve locally adapted seed varieties. Unfortunately, after the seed library came to the public’s attention, the Minnesota Department of Agriculture informed the library that they were in violation of a Minnesota statute that prohibited the exchange of non-commercial seeds. [xiv] Library Manager Carla Powers commented, “ . . . the law went so far as to make it illegal for gardeners to exchange a handful of seeds with one another” (Popovitch). But this did not end the library’s efforts. A number of ally organizations[xv] stepped up to create an amendment to the statute that exempted the exchange of non-commercial seeds from testing, labeling, and licensing laws. This inspired a state-wide effort to change the law. Duluth, Minneapolis, and St. Paul city councils all passed resolutions calling on the state to change its law, which was successfully accomplished in that year’s legislative session.[xvi]

Resistance to patented seeds and prohibitions against seed saving has risen around the globe in seed-saving farmers’ networks and seed banks. Here in Minnesota, Ojibwe bands throughout Minnesota requested that the U of M stop its genetic work on wild rice out of concern that GM wild rice plants would contaminate naturally occurring wild rice due to pollen being distributed through wind, water currents, and waterfowl. Receiving no response, they lobbied the state legislature, which in 2007 passed a law that stipulated regulations on the release of genetically modified wild rice. [xvii]

One of the largest resistance movements, the seed-saving network Navdanya in India, which is based on the Hindu principles of satyagraha -- holding firmly to the truth, and swaraj and swadeshi – self-rule, affirms farmers’ rights to determine their own lives and to produce, exchange, modify, and sell seed. “The seed has become the site and symbol of freedom in the age of manipulation and monopoly of its diversity,” wrote Shiva. “It embodies diversity and the freedom to stay alive” (Biopiracy, 126).

Probably the best-known seed bank is the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway, the world’s largest secure seed repository. Housed in vaults dug into the side of a mountain on a remote island in the Norwegian Svalbard archipelago, with the capacity to house 2.25 billion seeds, the vault currently stores more than 4000 plants in a natural deep freeze. Often referred to as the “doomsday vault,” it was created to secure a duplicate of every food seed from around the world – a bulwark against the worst, a promise of possibility for the future.

Every saved seed is a harbinger of hope. In a Women’s Studies senior seminar on motherhood, one of my students, Katie Witzig, combining her art and WS majors, created replicas of dozens of different kinds of seeds out of pottery. To her, the seed was the quintessential symbol of motherhood. Like mothers and fathers everywhere, the seed nourishes and keeps her offspring safe until it’s ready to be sent out into the world in hopes that it will flourish and contribute to the life and well-being of the world.

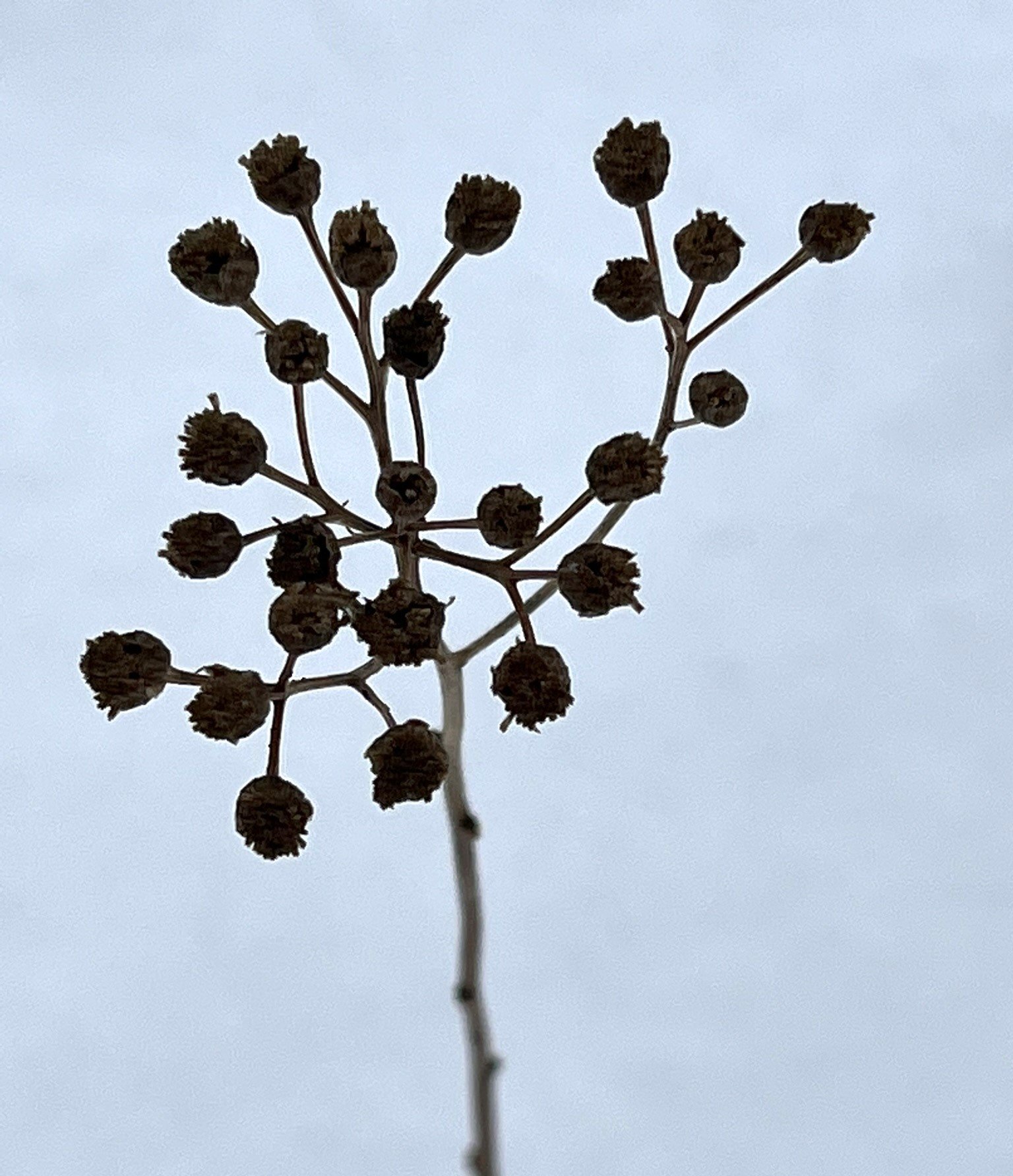

Seeds are the very essence of life and resilience. Even though it’s winter here now, and the ground covered with more than two feet of snow, the woods are filled with an abundance of seeds just waiting for the conditions to be right to be released into the world.

I’ll soon join them, starting seeds in little containers filled with soil, add a bit of water, warm them under the grow light, and hope. This year I’ll grow mostly heirloom varieties, which unlike the hybridized versions, can reproduce themselves year to year, and join the long tradition of saving seeds to be planted next year, when perhaps my then one-year-old grandson -- who now, like the seeds, is incubating safely inside his mother until the conditions are right for him to be born -- will help me plant the seeds I’ve saved for his future.

“People saved these seeds because they loved these seeds, and they thought we might love them, too . . . . Whoever saved the seed loved us before they knew us. . . .” – Ross Gay [xviii]

Sources

27 Organizations Working to Conserve Seed Biodiversity – Food Tank

Ananda Mohan ‘Al’ Chakrabarty 1938–2020 | Nature Biotechnology

Bouayad, Aurelian. April 2020. “Wild Rice Protectors: An Ojibwe Odyssey,” Environmental Law Review. Vol 22 25-42.

Camus, Albert. 1968. Lyrical and Critical Essays. Philip Thody, ed. New York: Vintage Books.

Cowden, Meg McAndrews. 2022. Plant, Grow, Harvest, Repeat. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press.

Duluth will be home to state's first public seed library | MPR News.

Gay, Ross. 2022. Inciting Joy. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books.

Goodall, Jane, with Gary McAvoy and Gail Hudson. 2005. Harvest for Hope: A Guide to Mindful Eating. New York: Warner Books.

Goodall, Jane. 2014. Seeds of Hope: Wisdom and Wonder from the World of Plants. With Gail Hudson. New York: Grand Central Publishing.

Hogan, Linda. 2020. “Ceremony for the Seeds.” in A History of Kindness. Salt Lake City: Torrey House Press.

Krause, Kea. “What Seed Saving Can Teach Us About the End of the World,” Orion. Orion Magazine - What Seed-Saving Can Teach Us About the End of the World.

LaDuke, Winona. 2005. Recovering the Sacred: The Power of Naming and Claiming. Boston: South End.

Popovitch, Trish. 2014. “The Seed Exchange Library that Fought the Law and Won” Seedstock. The Seed Exchange Library That Fought the Law and Won | Smart Cities Dive

Shiva, Vandana. 1997. Biopiracy: The Plunder of Nature and Knowledge. Boston: South End Press.

______. 1989. Staying Alive: Women, Ecology, and Development. London: Zed Books.

_____. 2000. Stolen Harvest: The Hijacking of the Global Food Supply. Boston: South End Press.

Steingraber, Sandra. 1997. Living Downstream: An Ecologist Looks at Cancer and the Environment. Reading, Massachusetts: Perseus Books.

[i] “In the depths of winter, I finally learned that within me lay an invincible summer.” Lyrical and Critical Essays, 169.

[ii] Despite the expiration date on my seed packets, this may be decades, or in the case of the date palm, “Methuselah,” thousands of years in the future. “Methuselah” – a Judean date palm found by archaologists studying the ruins of Masada from the time of King Herod was planted and it grew from the oldest seed to be woken. Others from 1300 years ago and 600 years ago have also bloomed.

[iii] Shiva, Stolen Harvest, 79.

[iv] 447 US 303

[v] 227 U.S.P.Q. 443 (Bd. Pat. App. 1985 granted patents on the tissue culture, seed, and whole plant of a corn line. It included 260 separate claims, granting the right to exclude others from use of all 260 aspects. Shiva, Biopiracy, 55.

[vi] According to a Department of Agriculture report, more than 18,000 plant patents were granted to inventors between 1990 and 2014.

[vii] Global Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (1947). The World Trade Organization (WTO) is the successor to GATT.

[viii] Shiva, Biopiracy, 79.

[ix] Bayer (which bought Monsanto in 2018), Corteva, ChemChina, and BASF. (Krause.)

[x] Shiva, Stolen Harvest, 80.

[xi] Krause.

[xii] LaDuke, 175.

[xiii] The Institute for a Sustainable Future, founded by Jamie Harvie, is based in Duluth, Minnesota. Its mission is to “support and improve ecological health through advocacy, research, consultation and education.” Institute for a Sustainable Future (ISF) (isfusa.org)

[xiv] Mn Statute 21.80-21.92.

[xv] The Institute for a Sustainable Future, St. Paul Ramsey County Food and Nutrition Council, St Paul’s West Side Seed Library and Do it Green! Minnesota all worked on legislation, and The co-chairs of Minneapolis Home Grown Food Policy Council, Russ Henry and Nadja Berneche of Gardening Matters acted as mediators during the process (Popovitch).

[xvi] The Minnesota seed laws can be read in full at the state’s Department of Agriculture website. The USDA provides a link to each state’s Department of Agriculture that show non-commercial seed exchange laws for the individual states. The Duluth Public Library was able to continue its seed library for about five years, but sadly eventually closed due to reduced staffing at the library and support from partner organizations. My thanks to Stacy LaVres who first told me about the Duluth Public Library seed library, found the pertinent article about it, and gave me other important information.

[xvii] While the legislation creates some protections, it does guarantee the safety of wild rice, which has now also come under threat by the degradation and pollution of wild rice lakes by Enbridge Line 3, which was constructed through wild rice lakes last year despite years of public hearings and public comment strongly opposed to the pipeline, as well as prayer and protest and water protector resistance. Those protecting the waters were arrested for defending the water and rice for us all. Many are still awaiting trial. In 2019, the White Earth Band announced the adoption of a Tribal ordinance entitled “Rights of Manoomin” (Bouayad).

[xviii] Inciting Joy, 36-37.