On Friday, January 23rd, seven hundred faith leaders from across the country heeded a call that had been put out just a few days before to come to Minneapolis to train, to observe, and to protest actions by ICE agents in the Twin Cities. Hundreds of them gathered in an interfaith service at Temple Israel. Others joined the National Prayer Call for Minnesota. And still others headed to the Minneapolis-St. Paul airport to engage in nonviolent direct action against the MSP airport authority, and Delta Airlines and Signature Aviation in particular, for their complicity with ICE in transporting those arrested either for deportation or for removal to other detention facilities.

While I was simultaneously livestreaming both the Temple Israel service and the National Prayer Call, my son was among those headed to the airport. In the midst of my concern for his and others’ safety from both the bitter cold – it was -40 below windchill – and from the violence of ICE agents, came the words of Rabbi Marcia Zimmerman offering a prayer for all those engaging in the protests that morning. In that moment, my anxiety eased as I could feel them all being surrounded by the prayer shawl of protection. Then, in a stunning moment of synchronicity, the cantor at Temple Israel sang while a Buddhist priest on the National Prayer Call invoked the blessings of Kuan Yin, goddess of compassion – the compassion that moved the protestors to act, but also that which surrounded the protestors with care. For while thousands engaged in protests that day – 50,000 at the march in sub-zero weather, and thousands more daily participate in protests on the streets and outside the Whipple Building – the ICE detention center in St. Paul, or act as constitutional observers throughout the Twin Cities and greater Minnesota, even more are engaged in daily acts of sustenance and care to support the protestors and those afraid to leave their homes for fear of being detained and disappeared by ICE. These acts of care are at the very heart of the resistance.

In her piece, “Homeplace: A Site of Resistance,” feminist scholar bell hooks wrote of the importance of homeplace – those domains of women “where all that truly mattered in life took place – the warmth and comfort of shelter, the feeding of our bodies, the nurturing of our souls”[i] – as sites of resistance. “There,” she continued, “we learned dignity, integrity of being; there we learned to have faith.” These were safe places where those wounded by racial domination, by othering, by dehumanization, could “restore to ourselves the dignity denied us on the outside by the public world.”[ii] These were places where spirits were nurtured and healed and solidarity was formed.

She went on to say that “when a people no longer have the space to construct homeplace, we cannot build a meaningful community of resistance.”[iii] ICE agents in the Twin Cities have been attempting to break down resistance by invading those homeplaces, going door to door, dragging residents from their homes, using battering rams to break down doors, detaining children and separating them from their homes, or by preventing people from providing the sustenance and nurturance of both food and community that they need by isolating them in their homes out of fear for their safety.

But rather than breaking the resistance, ICE actions have inspired it, and literally mobilized it, for when people have no longer been able to create homeplaces in their actual homes, in Minnesota, thousands of people are bringing homeplace to those in need. Mutual aid efforts abound. Many organizations help distribute food, diapers, and household goods to families isolated in their homes. Others help provide rent relief for those unable to leave their homes to work. Parents of children whose friends no longer go to school out of fear bring homework and school supplies and food to their children’s friends and their families, provide transportation, and arrange play dates so children can still be with their friends.

The minister of the UU church in the Twin Cities where my son is the music director was one of those 99 clergy who chose to be arrested at MSP airport. After she was processed and released, outside waiting she saw cars with “Safe Driver” posted on their windshields. She was greeted by a stranger with warmth, both physical and emotional, a cup of hot chocolate, and way to return to the church. At the church, many were busy providing homeplace in the kitchen there, and when the frozen congregants returned from the march that evening, a meal of hot soup, bread, and desserts awaited them – nurturance for the body and spirit.

A group that was originally formed to provide safety and support for domestic violence survivors has now become mobile support for those detained at the Whipple Building. When detainees, such as the many constitutional observers who are detained after legally following ICE vehicles, are discharged from the facility, they are typically are released into the freezing weather with no coats and no phones, since ICE confiscates these. One constitutional observer, a suburban mom, describing her detention experience to an MPR reporter, said she had no idea how she would get home or contact loved ones, only to be met immediately upon her release by a volunteer with this group, now Haven Watch,[iv] who gave her a coat, brought her into a warm vehicle, and provided a burner phone so she could contact her loved ones and get a ride home.

Even the National Guard in Minnesota protecting protestors outside the Whipple Building have been handing out coffee, hot chocolate, and doughnuts.

A new resistance action centered in homeplaces has sprung up in the wake of the ICE occupation in Minnesota. In a form of “craftivism” — a blending of craft with activism to make the world a better place through craft — the Minnesota yarn shop Needle & Skein has engaged knitters in a project of knitting red hats inspired by Norwegian resistance to Nazi Germany during WW II where Norwegians knitted and wore red hats with a tassel to protest Nazi occupation. So effective were they that Germany actually outlawed the hats after two years. Now hundreds of knitters in Minnesota and beyond are knitting these red hats. Proceeds from the sale of the patterns, now over $250,000, are going to support local immigrant organizations.[v]

Even on the day of horror following the National Strike and Day of Action in Minnesota, the day that Alex Pretti was executed on the street by ICE agents, Peter Anderson, one of the hundreds of clergy who came to Minneapolis for the Clergy Day of Action, reported that at the site where Pretti had been gunned down, “restaurants and churches opened their doors and supplies to feed people, warm people, and offer a safe place for medics and clergy to care for people. Kind people walking around offering cookies, samosas, granola bars, fruit snacks, water… whatever they can to nourish others. Tons of neighbors walking around with piles of hand warmers, making sure everyone is safe in the cold. People dedicated to helping others, showing up in their practiced roles… chaplains, medics, legal observers, runners, and more. A Free Table set out so people could share their supplies with others.”[vi] Even, or especially in that space of such violence --the feeding of bodies, the nurturing of souls, the restoration of dignity, compassionate care.

The Department of Homeland Security and ICE agents thought they could break the spirit of resistance in Minnesota. Instead, the community has responded by coming together, creating friendship and solidarity such as they’d never before experienced, and creating homeplace – “that space where we return for renewal and self-recovery, where we can heal our wounds and become whole”[vii] – whenever and wherever the need arises.

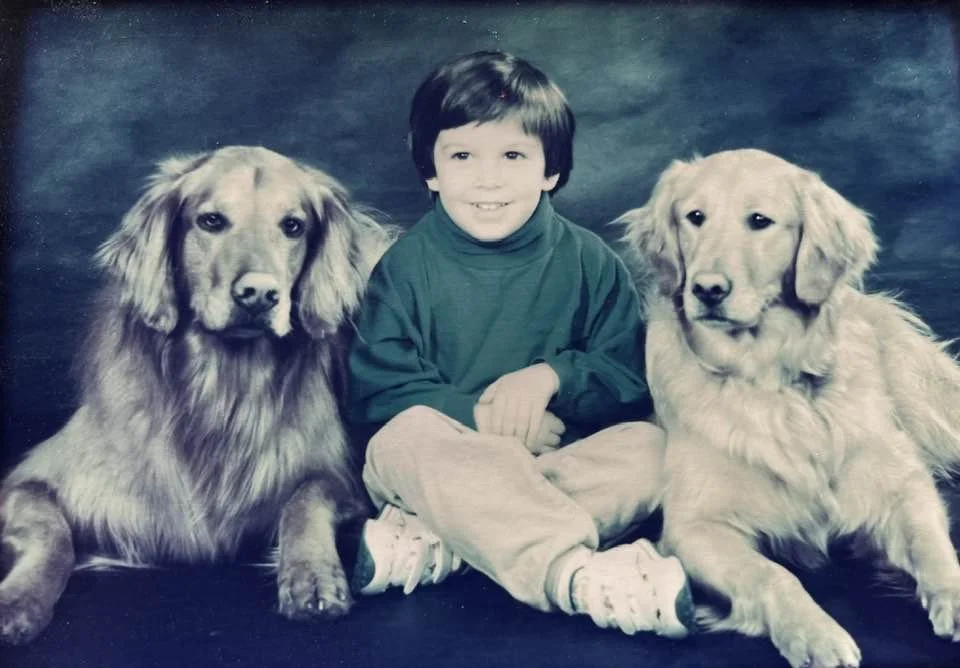

Mutual Aid for Minneapolis drop-off site at the Dovetail Cafe & Marketplace in Duluth.

Sources

Anderson, Peter. Facebook post. January 24, 2026.

hooks, bell. “Homeplace: A Site of Resistance,” in Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics. Boston: South End Press, 1990. 41-49.

Knitters resist ICE in Minnesota by making historic red hats

Minnesota National Guard hands out donuts, coffee to protesters in Minneapolis

Photo Credits: Thanks to Anna Rhode for permission to use her photo of the MSP Airport Protest, and to Dovetail Cafe & Marketplace for permission to use their photo of their mutual aid donation site.

[i] hooks, “Homeplace,” 41.

[ii] Ibid., 41-42.

[iii] Ibid. 47.

[iv] For more information, see Inside the group that helps ICE detainees released from Whipple find warmth, phones and rides | MPR News and Haven Watch

[v] For more information and to buy a pattern, see Knitters resist ICE in Minnesota by making historic red hats. As an added note, when I went to my local yarn shop to buy red yarn for the hat, they were completely sold the demand has been so great.

[vi] Peter Anderson, FB post, January 24, 2026.

[vii] hooks, 49.