I was lucky enough to be raised in a house filled with books. In fact, one of the rooms in our house was called “the library.” My parents’ bookshelves were filled primarily with religious texts by Biblical scholars; the living room with books on history and volumes of American Heritage; my brother’s bookshelves housed Compton’s Encyclopedia which I poured over time and time again; but the library was an eclectic mix of biographies, literature, books on raising children, books on nature and gardening, my father’s medical books that I loved perusing – especially Gray’s Anatomy with the layered transparencies of the human body, and My Book House books – books filled with children’s classics – from nursery rhymes to “Peter Rabbit” to “Rose White and Rose Red” to childhood biographies of authors (all of them white, most of them male.) My mother loved Tasha Tudor, and I developed a love for her illustrations as well – from her illustrated book of poetry to The Secret Garden to my favorite Christmas book -- A Doll’s Christmas. Unlike other girls at the time, I didn’t grow up on Nancy Drew or Laura Ingalls Wilder. Instead, my mom fed me with the “the little orange books” – childhood biographies of famous people -- Abe Lincoln, Jane Addams, and Clara Barton – that I read over and over again; a book of “heroines”-- including Harriet Tubman who inspired my first sermon at the age of ten; and a book on goddesses, where I first encountered the feminine divine in stories of Venus/ Aphrodite, Ceres/Demeter, and my favorite then and now – Diana/Artemis. My very favorite childhood books were The Witch of Blackbird Pond and The Diary of Anne Frank. Thus, it comes as no surprise that in my adulthood among the many books on my bookshelves are biographies and autobiographies of women and books on feminist spirituality and goddesses and political, racial, and feminist thought.

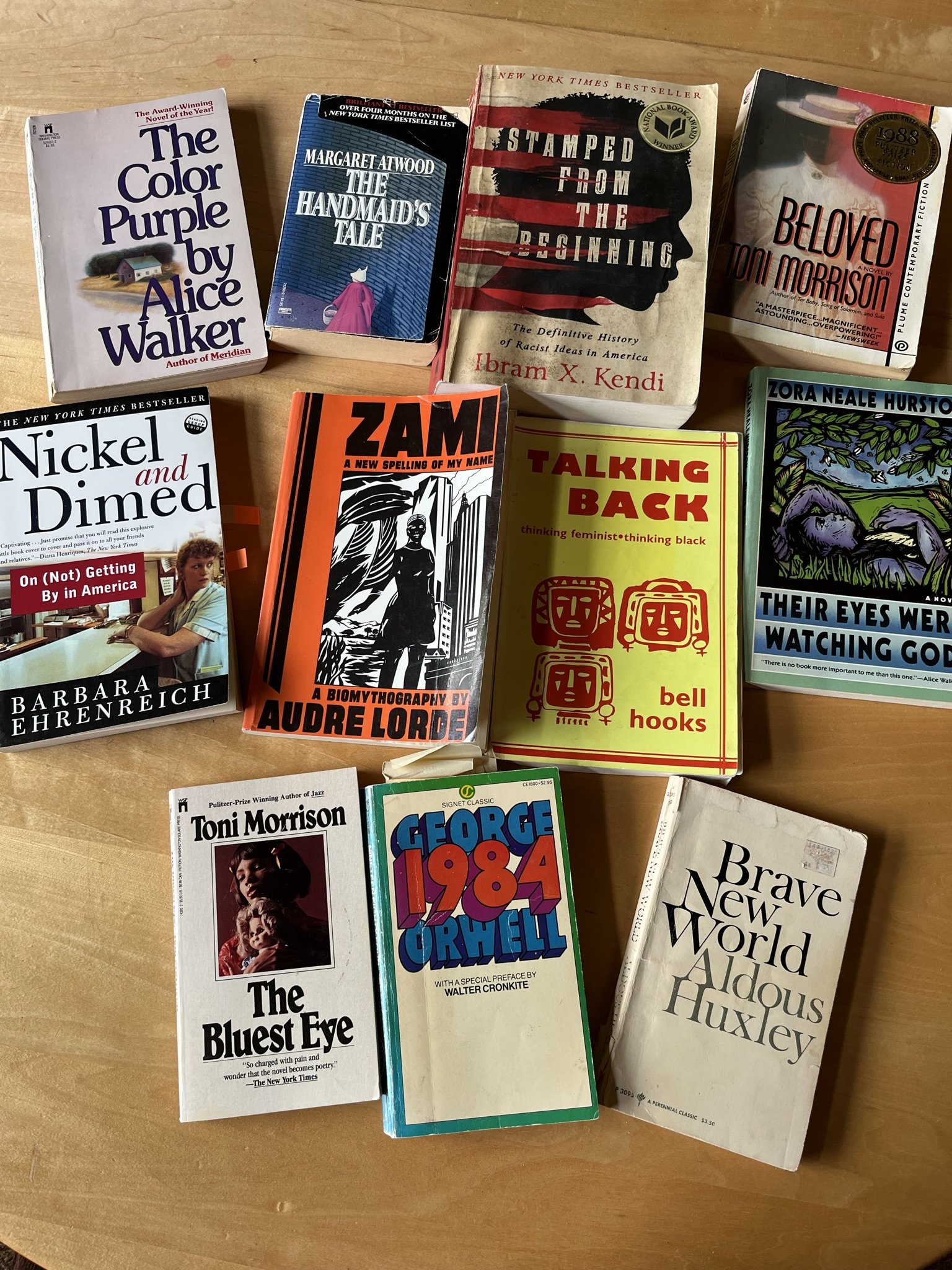

Books have in many ways been my best friends – friends who have put into words the truths of my body and soul, friends who have informed, inspired, challenged, enlightened, delighted, torn me open, gutted me, kept me the best of company, and helped me to understand myself and the world. Is it any wonder then that my whole body reacts in horror at the wave of book bannings happening in schools and libraries across this country. Many of the banned books were required reading in my high school -- George Orwell’s 1984 and Animal Farm; William Golding’s Lord of the Flies; John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, Richard Wright’s Native Son and yes, The Diary of Anne Frank. Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 was required of all first-year-students when I started college. Many are books I’ve required students to read -- 1984, Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, Barbara Ehrenreich’s Nickel and Dimed, Alice Walker’s The Color Purple, and the works of Audre Lorde and bell hooks. I imagine nearly all the books I’ve had students read over the years would be banned if they were popular enough to come to certain officials’ attention, since most of the books currently being banned explore LGBTQ, racist, and sexist oppression; racial justice; and feminist topics. Many are books that have most enlightened me -- Nikole Hannah-Jones’ The 1619 Project, Zora Neale Houston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God, Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye and Beloved, Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, Malcolm X’s The Autobiography of Malcolm X, Kate Chopin’s The Awakening, Ibram X. Kendi’s Stamped from the Beginning (which should be required reading of everyone in this country.)

It's certainly not the first time books have been banned, burned, or otherwise destroyed. Most have been for religious reasons – destroying books considered to be “heretical,” at odds with the ruling faith. The Bible itself as we know it today was created through a process of a winnowing out of the controversial books down to 66 books. We have some idea, but mostly don’t know exactly what was discarded, but in 1945, Muhammed ‘Ali al-Sammãn discovered an earthenware jar in a cave near the town of Nag Hammadi in Egypt containing thirteen bound papyrus books. In all, fifty-two writings were discovered at Nag Hammadi. Now known as the Gnostic Gospels, these were some of the texts condemned as heresy by orthodox Christians in the mid–second century. Among other things, they raise controversies about Jesus’s resurrection, the role of Mary Magdalene, Sophia and God as mother, and self-knowledge as knowledge of God. One wonders who buried them and what knowledge they hoped to keep alive in the event of their discovery. What other scrolls might have been buried? What truths have been burned and discarded? How might have Christianity and its role throughout the world been different had these not been hidden?[i]

Nazi students burning books in 1933

Probably the most infamous of book burnings are those of Nazis in Germany in the 1930s. Among the first books burned were those akin to those being banned in the US today -- books on homosexuality, intersexuality, and transgender – when the Institute of Sexology was burned to the ground. This was closely followed by burning books by Jewish and leftist authors – from Albert Einstein and Sigmund Freud to Ernest Hemmingway and Helen Keller. Thus does totalitarianism begin with the destruction of competing ideas, with destruction of the truth.

But that was Nazi Germany. It couldn’t happen in America, right? I recently saw a post on Facebook quoting the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression which said that banning books is unAmerican, but unfortunately, it’s quite American. Just as books in the US critical of systemic racism are being banned now, books critical of slavery were banned in the South with the rise of abolitionism, with Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin topping the list. In the 1870s, the Comstock Society’s desire to rid the nation of “lewdness” led to massive book burnings, and the Comstock Law[ii] has led to a variety of books being banned over the decades. Its legacy is alive and well in the banning of so many books in the US today -- from Gender Queer to All Boys Aren’t Blue to Sold -- on the basis of depictions of sexuality.

But resistance to book banning is also American. In Arkansas, the Central Arkansas Library System, and a coalition of other libraries, are protesting the law recently signed into law by Gov. Sara Sanders, that makes it possible to imprison librarians for giving materials deemed inappropriate for minors to children, arguing that it violates the First Amendment. In Illinois, the legislature has passed a bill that blocks community and public-school libraries in the state from receiving certain types of funding if they ban books, in effect imposing a monetary penalty on institutions that go along with book banning. During the month of May, the New York Public library, through an initiative called Books for All, made commonly banned books available to all readers aged 13 and up, whether or not they had a library card.

I hadn’t intended this to be a post about book banning. I had intended to share more in depth about many of the books I have loved, and undoubtedly this post needs a Part Two, if not Parts Three and Four. But I trust the process of writing to reveal what needs articulation. I also came to realize that much of this blog is already about sharing the books which have so informed my life, raised my curiosity, enriched my life.

However, something I read in Frédéric Gros’s A Philosophy of Walking disquieted me. He writes, “Our first question about the value of a book . . . is can [it] walk? Books by authors imprisoned in their studies . . . are heavy and indigestible. They are born of a compilation of other books on the table [often piled high on the table in front of me as I compose these posts.] They are like fattened geese: crammed with citations, stuffed with references, weighed down with annotations. . . . Books made from other books, by comparing lines with other lines, by repeating what others have said [as I am doing here] . . . remain on the level of recopying” (19-20). But, he continues, books that arise from “an author who composes while walking . . . are light and profound” (20).

I have written books like the former (academia will do that to you), and books like the latter, just as I’ve written posts like the former, and posts like the latter. This blog began as a way to share ideas and insights, primarily from the books that have moved me, and their conversation with each other. I’ve always found the interweaving of books and ideas to result in a synthesis that reveals novel and often exciting perspectives -- hopefully something that is other than simply “recopying.” I share citations in part so that others may seek out the source and draw their own conclusions. The actual writing in my mind often takes place while walking, so perhaps occasionally the compendium of ideas rises above “heavy and indigestible.”

I am grateful to the books and authors that have walked with me through this life, to the many who have placed just the right book in my hands at just the right time, and to all who share this love of books – bibliophilia (even though MS Word doesn’t recognize it as a word!) – with me.

Sources

Arkansas librarians say it's unconstitutional that they can be jailed over books (msn.com)

Book bans: Illinois poised to be first state to punish libraries that remove titles (msn.com)

Book Burnings in Germany, 1933 | American Experience | Official Site | PBS

Gros, Frédéric. 2015. A Philosophy of Walking. Trans. John Howe. London: Verso.

New York Public Library makes banned books available for free : NPR

Pagels, Elaine. 1979. The Gnostic Gospels. New York: Vintage Books.

The 15 most banned books in America this school year - Los Angeles Times (latimes.com)

Top 100 Most Banned and Challenged Books: 2010-2019 | Advocacy, Legislation & Issues (ala.org)

[i] In her conclusion, Pagels suggests that had Christianity retained its multiple forms, it may have taken a very different role in the world, and may even not have survived at all. She posits that it is fortunate that the scrolls were found in the 20th century, arguing that had they been found 1000 years earlier, they most likely would have been burned for heresy. She said that in the 20th century, we have a new perspective that enables us to appreciate them as a “powerful alternative to the orthodox Christian tradition” (151). Today, I wonder what might have become of them had they been found in this 21st century when books are once again under scrutiny for being heretical to the chosen faith of some.

[ii] The Comstock Law of 1873 made illegal the selling or sending of anything considered “obscene,” including information on contraception and abortion.