By breath, by blood, by body, by spirit, we are all one.

The air that is my breath . . . is the air that you are breathing./ And the air that is your breath . . . is the air that I am breathing./ The wind rising in my breast . . . Is the wind, from the east, from the west,/ From the north . . . from the south; Breathing in, breathing out.

So begins singer-songwriter Sara Thomsen’s song, “By Breath,” bringing together many elements I’ve been pondering in the last several days – breath, air, wind, spirit.

In cultures around the world, each of the four seasons is associated with one of the four cardinal directions and one of the four elements – earth, air, fire, water. In this season of winter, the associated direction is north, and the element is air. In these last few days of wild winter, the air from the north has indeed been making its presence known. The wind has been fierce, powerful, sculpting the snow into huge drifts and whipping up waves on the great lake, forming cliffs of ice on the rocks that line the shore. It is as if these last gasps of winter are saying, “Air is my element and wind my breath. Remember the air is sacred.”

The sheer force and power of the wind has often been associated with the divine — “And there went forth a wind from the Lord . . . “ (Numbers 11:31); “See, the Lord has one who is powerful and strong. Like a hailstorm and a destructive wind” (Isaiah 28: 2); “Therefore this is what the Sovereign LORD says: In my wrath I will unleash a violent wind” (Ezekiel 13:13). Or as novelist Zora Neale Hurston wrote in describing the coming of the great Okeechobee hurricane, “The wind came back with triple fury, and put out the light for the last time. They sat in company with the others in other shanties, their eyes straining against crude walls and their souls asking if He meant to measure their puny might against His. They seemed to be staring at the dark, but their eyes were watching God” (151-152).

So often on my winter walks, I find myself bracing against the wind, fending off the biting cold, made even sharper by the wind. But in the course I’ve been taking on “rewilding,” one of the practices suggested for winter is to engage the wind, rather than buffer against it, and see how that shifts one’s experience of the season. Indeed, on the day I participated in this practice, I found my spirit enhanced, lightened, inspired. Spirit – from the Latin spiritus, meaning “spirit, soul”; inspire, inspiration – also from the Latin inspiritus, meaning “to breathe into, to inspire,” and in English – “to draw breath into the lungs.” Here is yet another understanding of air as sacred, as divine, as spirit, and as inspiration -- the divine expressing itself through us.

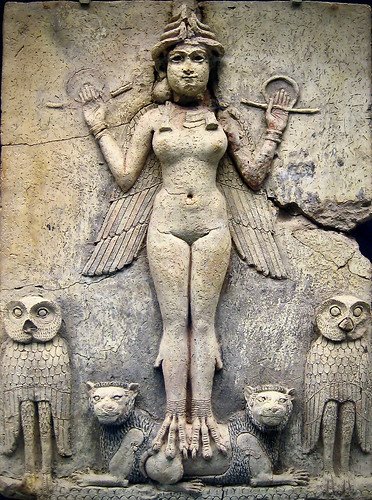

The Hebrew word for breath is the same as the word for spirit –ruach. The spirit is invoked in the beginning -- “ . . . and darkness was over the surface of the deep, and the Spirit (Ruach) of God was hovering over the surface of the water” (Genesis 1:2). The word ruach is feminine, and the Holy Spirit is often regarded as the feminine divine, which is so often represented in creatures that fly through the air and glide on its currents — birds. In the case of the Holy Spirit, it is a dove, but we have unearthed so many others in archeological digs and ancient legends – the Minoan bird goddesses, the winged Isis, the Sumerian Lilith, the Celtic Rhiannon. As artist Judith Shaw wrote, “. . . from the great quantity of statues found . . . it is easy to believe that the Bird Goddess was seen as a divine being who nurtured and protected the world.” She goes on to say that the ancient Bird Goddess ruled over life and death – the first breath and the last.

Much has been written about the last breath, but not about the first. About the same time, perhaps even the same day as I practiced engaging the wind, I happened to listen to a re-broadcast of an episode of NPR’s Radiolab on “Breath.” It began with an explanation of the ingenious, miraculous first breath in which we humans transition from water-dwelling beings in the watery womb to air-dwelling beings outside in the world. In the water-dwelling fetus, the lungs have no function. Instead, the fetus gets its oxygen from its mother through the placenta and umbilical cord, the oxygenated blood flowing directly from the right to the left chambers of the heart through a hole -- the patent foramen ovale -- bypassing the lungs that in fetuses are filled with water. But in the split second of that first breath, the umbilical cord shuts down the flow of oxygenated blood and the patent foramen ovale closes, requiring that the once water-filled lungs now be filled with air. The right and left sides of the heart now forever closed off from each other, from now on, the oxygen-deprived blood that flows into the right side of the heart must now be pumped out of the heart into the lungs where it is enriched with oxygen, and then returns to the left chambers of the heart where it is then pumped to every tissue in our bodies. That first breath enables the continual flow of in-breath and out-breath, for most of us about 500 million times in our lifetimes. I will never forget that first breath of my own child as he came into the air-breathing world. That first cry remains, and always will, the sweetest sound I have ever heard. Aware now of all that happens with that first breath, I am filled with an even deeper awe.

Most of the time we breathe without thinking. Regulated by a pacemaker in the brain, our breathing mostly happens on its own without our conscious effort. We can so easily forget the preciousness of our being able to breathe — until we can’t. As a child with asthma, I early on had a bodily awareness of how easily breathing could become difficult, and at times impossible. So many suffer from impaired breath --whether from lung disease, or polluted air, or the choking smoke of wildfires which are becoming larger and more frequent. I remember vividly when indigenous elders who had traveled here from British Columbia for a training in which I participated, told us of how the fires there were so intense that they had been forced to stay inside much of the month of August. They had hoped to be able to get a breath of fresh air here in Duluth. Instead, they found that even here, a few thousand miles distant, the smoke from those same fires could be smelled and filled the sky with a lingering haze. We are all breathing the same air.

Just as we are all breathing the same air of systems of oppression – of patriarchy, hierarchy, mind/body value dualism, [i] and as Isabel Wilkerson has enlightened us, of caste. As I write this, the words of George Floyd pinned under Derrick Chauvin’s knee — “I can’t breathe” — echo in my mind. The same paradigm of Western thought that ranks human beings above “nature” (as if we were not nature), allowing us to degrade the atmosphere, ranks some human beings above others, contributing to the poisoning of all our relations.

Will we rise to the best of our possibilities, to join those whom Albert Camus called the “true healers” – those who refuse to be cast among the “victims” or the “pestilences,” but rather seek to help those struggling to breathe – whether literally or metaphorically? We see them on the front lines of those who would protect the earth – the water protectors at Standing Rock and Line 3, the forest protectors at Cop City[ii], the Greenpeace activists across the globe demanding “Clean Air Now,”[iii] the young people raising the alarm on climate change; we see them among those who would disrupt the foundations of these systems -- whether in the streets or in courtrooms or in the writings and voices of the historians and the seers -- Nikole Hannah-Jones, Ibram X. Kendi, Isabel Wilkerson, Susan Griffin, Gerda Lerner, Robin Wall Kimmerer[iv]; just as surely as we saw the paramedics, the respiratory therapists, the doctors and nurses on the front lines of the pandemic. [v] It is so fitting that “I can’t breathe” has become the rallying cry of those demanding a just world where all can breathe.

Soon, my first grandchild will take that first precious breath. As I look into his future, I wonder, what will be the quality of the air that he — and all beings — breathe? In what atmospheres will we dwell? Perhaps the answer lies in the quality of all our relations.

“They say our fate is with the wind,” writes ecofeminist Susan Griffin. She asks, “Will we take what the wind gives, or even know what is given when we see it? . . Do our whole bodies listen? . . . Can we give to the wind what is asked of us? . . . will we be able to hear the wind singing and will we answer? Can we sing back?” (222).

What will be the nature of our song? Will we learn . . .

By breath, by blood, by body, by spirit, we are all one.

Sources

“Breath.” June 11, 2021. Radiolab.org

Camus, Albert. 1948. The Plague. Trans. Stuart Gilbert. New York: Random House.

Griffin, Susan. 1978. Woman and Nature: The Roaring Inside Her. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers.

Hurston, Zora Neale. 1937, 1990. Their Eyes Were Watching God. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers.

Shaw, Judith. “The Bird Goddess.” Feminism and Religion Blog Post. November 23, 2016. The Bird Goddess by Judith Shaw (feminismandreligion.com)

Thomsen, Sara. 2003. “By Breath.”

Wilkerson, Isabel. 2020. Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents. New York: Random House.

[i) Mind-body value dualism is the system of Western thought in which related pairs of things are arbitrarily posited as opposites — in this case mind and body, with the mind being valued more than the body. What follows is that those things associated with the mind are valued more than those things associated with the body — men vs. women, humans vs. animals, white people vs. BIPOC persons, culture vs. nature, humans vs. nature, Western/Euro vs. “Third World,” colonizer vs. colonized.

[ii] Cop City is the name forest protectors have given to a proposed training complex for police and fire fighters that if constructed would require the razing of an 85-acre old growth forest outside of Atlanta, Georgia.

[III] Our global movement against air pollution - Greenpeace International

[iv] These are among the dozens of scholars who have delved into the depths of the foundations of these systems of oppression. Nikole Hannah-Jones is the journalist behind The 1619 Project. Ibram X. Kendi is the author of among others, Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America; Isabel Wilkerson is the author of Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents; Susan Griffin is an ecofeminist essayist and poet and author of among others, The Chorus of Stones: The Private Life of War and The Eros of Everyday Life. Gerda Lerner was the premiere historian of women’s history, and author of The Creation of Patriarchy. Robin Wall Kimmerer is the author of Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. Reading the works of these authors would begin to give more depth to our understandings of the foundations of systems of oppression and how we might achieve a truly egalitarian society.

[v] As a side note, I cannot begin to express my gratitude to those strangers, paramedics, doctors, and nurses who have literally breathed their breath into my lungs when I have suffered respiratory and cardiac arrests and my own breathing had stopped. I owe the fact that I am alive and breathing to all of those who enabled me to breathe.