“My first step from the old white man was trees. . .” – Alice Walker

The image of God presented to me as a child was more of a loving father than an old white man in the sky, but that image was so pervasive in Western culture, I’m sure it gained some sort of symbolic purchase in my understanding of the divine. I also grew up with the belief that Jesus was both the Son of God and the divine himself. Whether as God or Jesus, the divine definitely was male, and transcendent. The Lord’s Prayer, said weekly in our church, began “Our Father,” and then “who art in heaven,” which in my childhood imaginings must have been in the sky. My favorite hymn as a child was “This Is My Father’s World,” -- definitely God as a father figure, but what I loved most in that hymn were the lines:

. . . And to my list’ning ears

All nature sings, and round me rings

The music of the spheres.

. . . I rest me in the thought

Of rocks and trees, of skies and seas—

. . . The birds their carols raise,

The morning light, the lily white,

. . . In the rustling grass I hear Him pass,

He speaks to me everywhere.

So perhaps my first step from the Old White Man was indeed the trees, and rocks and birds and seas. I always felt closer to God in the small chapel built in the woods behind our church, on Vesper Hill at the church camp where I was both a camper and counselor and our early Morning Watch when we would begin each day in solitude in the camp woods and meadows, and in childhood moments in cathedrals of pines and baptismal waters of lakes.

But it was not until much later, in the midst of my feminist awakening, that I became aware of writers, scholars, and theologians who spoke to my experience of the divine in nature. Starhawk’s The Spiral Dance and Matthew Fox’s Original Blessing were circulating in my feminist community at that time. Both imaged the divine not as male, nor as transcendent, but as God/dess and immanental. Fox’s panentheism – the divine alive in all things – resonated deeply in me. But it was Carol Christ’s “Rethinking Theology and Nature” that created a paradigm shift in me. Reading her lines, “There are no hierarchies among beings on earth. . .” (321) shattered any remaining illusions I had continued to hold of humans being superior to other animals and animals to plants and plants to rocks and water and soil. I have walked through the world differently ever since. Her eloquence in describing the intrinsic beauty and value in every being cemented my understanding of the divine as immanental – within all beings on earth and the earth itself.

But the nature of the divine as male still had a foothold in me. It was Carol Christ’s piece, “Why Women Need the Goddess,” that affirmed my need to immerse myself in the study, language, and invocation of the goddess/es. As Christ wrote, “Because religion has such a compelling hold on the deep psyches of so many people, feminists cannot afford to leave it in the hands of the fathers” (Laughter, 118). That hold is created particularly by the power of the symbolism of the male divinity of God the Father that continues to operate even in those who consider themselves fully secularized. Christ argued that because religion reaches people at such a deep psychic level and fulfills such important needs to cope with suffering and evil, birth and death, it functions at a symbolic rather than a rational level. The God the Father symbol continues to have an effect because “…the mind abhors a vacuum.” She continued, “Symbol systems cannot simply be rejected, they must be replaced. Where there is not any replacement, the mind will revert to familiar structures at times of crisis, bafflement, or defeat” (Laughter, 118). Her piece gave me the permission and the motivation I needed to replace all references to God as male, father, lord, and king with goddess as female, mother, and sister within in language and imagery, and as recipient of my prayers.

Venus of Willdendorf

I changed the male language in every hymn I sang and every prayer I spoke. At feminist spirituality conferences, with hundreds of other women, I invoked, “The earth is my sister, I must take care of her.” With Starhawk, I danced the Spiral Dance, chanting, “She changes everything she touches, and everything she touches changes.” Riane Eisler’s The Chalice and the Blade introduced me to the thousands of years of goddess-worshipping cultures that lived in peace and partnership and celebrated the feminine divine. I immersed myself in the study of these cultures and the feminine divine, in the goddess imagery found throughout the world, in contemporary goddess chants and medieval mystic Hildegard of Bingen’s music and art celebrating the feminine divine. I discovered and embraced as well the feminine divine within my own Judaeo-Christian religious upbringing – the Jewish Shekinah and the Christian Sophia or Wisdom. To read descriptions of these figures of the feminine divine was transformational for me, enabling me, in the words of Ntozake Shange to find “. . . God in myself, and I loved Her, I loved Her fiercely” (63).

Shekinah is She Who Dwells Within/The force that binds and patterns creation . . . Shekinah is Changing Woman, Nature herself/Her own Law and Mystery/She is cosmos, dark hole, fiery moment of beginning./She is dust cloud, nebulae, the swirl of galaxies/She is gravity, magnetic field,/The paradox of waves and particles. . . . Creatrix of complex systems/Expanding, contracting, spiraling, meandering/The beginning of Wisdom. – from the Kabbalah (Gottlieb,26-27)

Wisdom, the artificer of all, taught me. For in her is a spirit, intelligent, holy, unique, manifold, subtle, agile, clear, unstained, certain, not baneful, loving the good, keen unhampered, beneficent, kindly, firm, secure, tranquil, all-powerful, all-seeing, and pervading all spirits, though they be intelligent, pure and very subtle. Indeed she reaches from end to end mightily and governs all things well. Wisdom: 7: 22-23

The words parallel those of Paula Gunn Allen: There is a spirit that pervades everything. . . . She appears on the plains, in the forests, in the great canyons, on the mesas, beneath the seas. To her we owe our very breath. . . . She is the true Creatrix . . . She is the necessary precondition for material creation, and she, like all of her creation, is fundamentally female – potential and primary (22).

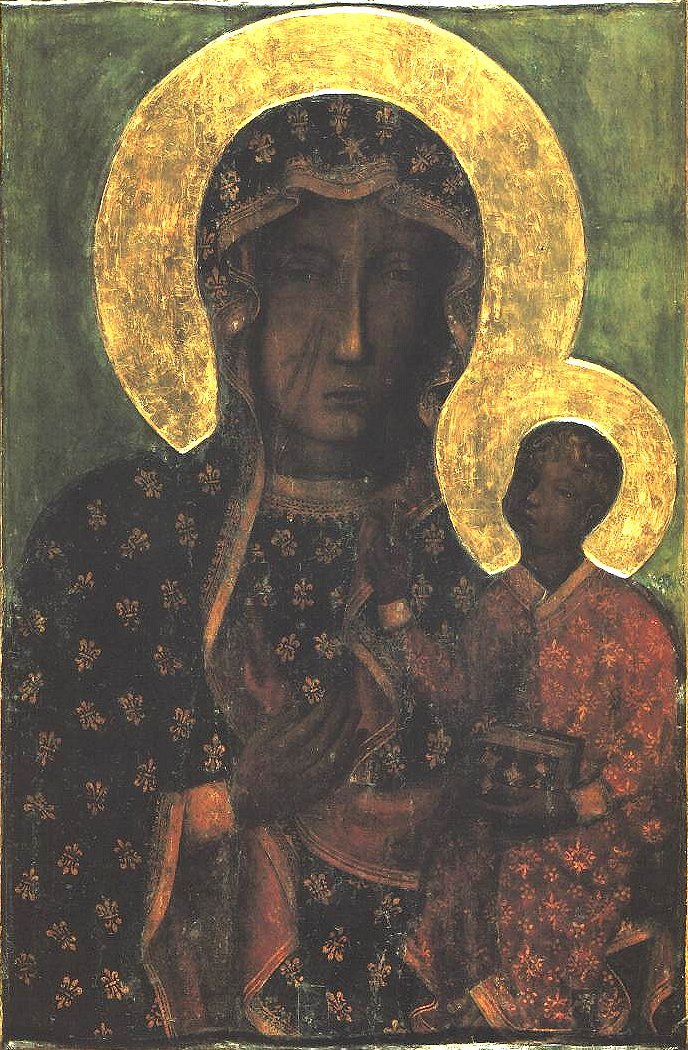

Black Madonna of Czestochowska

China Galland expanded my notion of the feminine divine through her exploration of the Buddhist Tara -- the very essence of compassion, and the veneration of the Black Madonna, inspiring thousands to travel in pilgrimage to various shrines to her throughout Europe to this very day. Galland described this as “longing for darkness” which, she said, is to long “for transformation, for a darkness, that brings balance, wholeness, integration, wisdom, insight” (152). Elizabeth Schussler Fiorenza said the same of the original followers of Jesus -- that in the early Jesus movement, Jesus’s disciples understood Jesus as one of a long line of prophets of Sophia sent to bring back balance, and restore wisdom, mercy, kindness, and justice. The world is sorely in need of the rebalancing energy of the feminine divine.

But my conception of the divine did not settle here. Carol Christ continued to push my thought. Her She Who Changes caused yet another paradigm shift in me. In it, Christ systematically explored what Charles Hartshorne identified as the six theological mistakes of classical theism: 1) God is perfect and unchangeable; 2) omnipotence, 3) omniscience, 4) God’s unsympathetic goodness, 5) immortality; and 6) revelation as infallible. While I was in complete agreement with her arguments that the divine is not omnipotent, omniscient, nor unsympathetic, the notion of divine as changeable rocked my world. It both made sense and no sense at all. Wasn’t the divine this one constant in the world – this unceasing loving presence? And yet, as is so often said, the only constant in life is change itself.[i] Hadn’t my own conception and connection with the divine changed so many times in my lifetime? The notion of the divine as “she who changes” was at once unsettling and expansive. The more I pondered, the more liberating it felt to understand the divine as always in process, allowing for becoming. At the time I read She Who Changes, I had only recently become aware of the process philosophy in which Christ based her work, but for years I had been engaging in process psychology. “Trust the process,” my therapist would say. I had learned to put my faith in the process. Was this not the notion of the divine as changing – trusting that the process would bring me to the divine within?

Yet Christ also described her own experience of the divine as “always there” (Christ & Plaskow, 261). In being with her mother in her dying, Christ had discovered “that a great matrix of love had always surrounded and supported my life” (Rebirth, 4.) Her words gave expression to my own experience. Christ explained this constancy of the changing divine through Hartshorne’s concept of “dual transcendence” -- that while the divine is always in a process of change, co-creating with a changing world, the nature of the divine remains the same. In this, which I believe would more appropriately be called “transcendence in immanence” or “immanence in transcendence,” Christ succeeded in breaking and blending the very dualisms she had sought to transform.[ii]

My understanding of the divine now is fluid – a loving presence, an energy uplifting and supporting me and life on earth and in the universe, the divine spark within all of life – as constant as the sun rising each day and as changeable as each sunrise is from day to day and moment to moment.

Sources

Allen, Paula Gunn. 1989. “Grandmother of the Sun: The Power of Woman in Native America.” In Plaskow, Judith and Carol P. Christ. Weaving the Visions: 22-28.

Babcock, Maltie D. 1901. “This Is My Father’s World.”

Christ, Carol P. 1987. Laughter of Aphrodite: Reflections on a Journey to the Goddess. San Francisco: Harper & Row.

______. 1997. Rebirth of the Goddess: Finding Meaning in Feminist Spirituality. New York, Routledge.

______. 1989. “Rethinking Theology and Nature.” In Plaskow, Judith and Carol P. Christ. Weaving the Visions: New Patterns in Feminist Spirituality. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco: 314-325.

______. 2003. She Who Changes: Re-Imagining the Divine in the World. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Christ, Carol P. and Judith Plaskow. 2016. Goddess and God in the World: Conversations in Embodied Theology. Minneapolis: Fortress Press.

Eisler, Riane. 1988. The Chalice & The Blade: Our History: Our Future. San Francisco: Harper & Row.

Fiorenza, Elizabeth Schussler. 1984. In Memory of Her: A Feminist Theological Reconstruction of Christian Origins. New York: Crossroad Press.

Fox, Matthew. 1983. Original Blessing: A Primer in Creation Spirituality Presented in Four Paths, Twenty-Six Themes, and Two Questions. Santa Fe: Bear & Co.

Galland, China. 1990. Longing for Darkness: Tara and the Black Madonna. New York: Penguin.

Gottlieb, Lynn. 1995. She Who Dwells Within: A Feminist Vision of a Renewed Judaism. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco.

Plaskow, Judith and Carol P. Christ. 1989. Weaving the Visions: New Patterns in Feminist Spirituality. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco.

Shange, Ntozake. 1975. For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Is Enuf. New York: Scribner.

Starhawk. 1979. The Spiral Dance. San Francisco: Harper & Row.

Walker, Alice. 1982. The Color Purple. New York: Washington Square Press.

[i] This saying is first attributed to the Greek philosopher, Heraclitus. Who Said "the Only Thing Constant Is Change"? (reference.com)

[ii] See especially her Rebirth of the Goddess, 98-104.