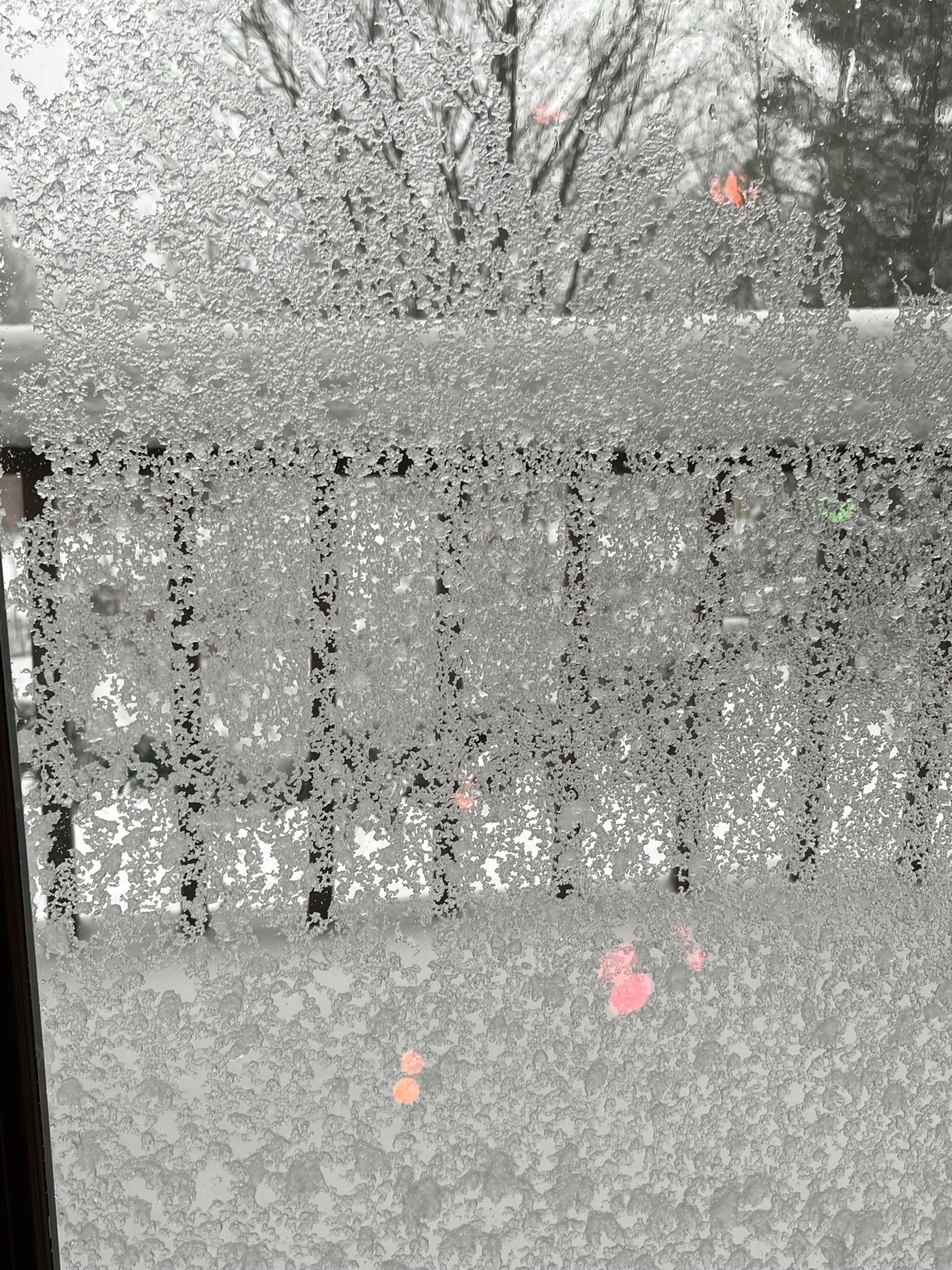

The wind has been howling all night and snow and ice have covered the windows to the point we can barely see through them. We are sixteen hours into a 48-hour blizzard. Outside the snow is swirling, blasting the tree trunks so they are completely white and snow-covered on their eastern side. There’s hardly a creature out, though our dog needed walking, and more birds are gathering at the feeder than I’ve seen all winter. Late last night, I watched a doe and stag walk slowly down the middle of our street, perhaps enjoying the dearth of cars and having a somewhat clear path. Hopefully they were on their way to some shelter from the warmth.

I wonder about all those without shelter in this storm. The Warming Center provides a place to get out of the snow and cold to those who are unhoused from 6 PM to 8 AM, but I’m hoping it will stay open all day for the duration of this storm. The song, “Oh the weather outside is frightful, . . . as long as we’ve no place to go, let it snow!” keeps playing in my mind, and I find myself thinking of those with no place to go to get warm and dry. I, on the other hand, am fortunate to be inside a cozy warm home, where “in here, it’s so delightful” – a fire blazing in the fireplace, a Christmas tree lit up in good cheer, my dog snuggled up on the couch next to me, plenty of food and all the meds I need, a pile of good books – and no place to go. This morning a friend posted a desperate need for a jigsaw puzzle to ride out this storm, and I even have plenty of those, even a couple new ones. I feel considerable gratitude to be safe and warm on this blustery day.

Halloween Blizzard 1991

My mind travels back to the Halloween blizzard of 1991. Our little boy was two, and eager to be out in his red snowsuit with his little red snow shovel, helping his dad shovel the long, steep driveway. (After that blizzard, we went in with the neighbors across the street to get a monster snow blower that we shared for many winters.) I, on the other hand, was stuck inside with a broken heart – literally. My heart had been damaged years before, most likely by an infection, and it was at the end of its run. I had an implanted automatic defibrillator that would shock my heart if my heart rate went too high or went into fibrillation, so I waited out those four days before we were plowed out in mild terror that the defibrillator would go off, and I’d be stuck being shocked over and over without access to an ambulance or hospital. I well remember the relief when finally the roads were plowed, but even more so, the jubilation I felt during the first big storm after my transplant, when I could just go out and play in it.

One winter of several storms, I read Laura Ingalls Wilder’s The Long Winter every night to our young son at bedtime. Reading the narratives of total whiteout, nearly getting lost in the short distance between the house and the barn, being almost without food toward the end of the winter, and snow upon snow upon snow felt like it was prolonging what had become a seemingly endless winter for us as well. But again, unlike the Ingalls, we had the gifts of food and warmth.

Thinking of those days of early white settlers in Minnesota, I wondered about how the earlier indigenous peoples of this place endured these storms. For the Anishinaabe, winter – biboon -- is the time to gather inside and tell stories. In her book, Onigamiising, my friend, Linda LeGarde Grover, wrote that by doing so, they are honoring their ancestors by passing along their spiritual teachings and stories of survival from generation to generation. She also shared that she had been told that one of the reasons that winter was the story-telling time is that, because some of the stories involve animals who are asleep during the winter, “they won’t hear us talking about them; we are being considerate of their feelings” (160). One of her favorite stories was one about how Gaagoons, the porcupine, scares off bullies with help from Nanaboozhoo. She said that what she loved about that story is the way Gaagoons maintains his “gentle and kindly ways” after he becomes a great warrior. The story reminds me of Linda herself, retaining her gentle and kindly ways, even after becoming a great warrior poet.[i]

“Biboon,” she writes, “is a time to appreciate the closeness of home” (147). With the blizzard raging outside, I am appreciating that more on this day than I usually do. Assuming the power stays on – we are hoping against hope that it does – soon I’ll bake muffins and venture out into the wild with my dog, Ben -- like Gaagoons, braving the bully winds — to take the muffins to a neighbor who is alone for the first time this winter. Later it will be time to break out a new puzzle, make a home-made pizza (though the recipe for a hotdish that Linda shared in her book made me hungry for tuna noodle casserole), perhaps watch a Christmas movie together with my husband, and nestle under the covers, grateful for shelter from the storm, hoping that all – from deer to squirrels to feathered ones and unhoused men, women, and children – also have a warm place to be tonight.

Source

Grover, Linda LeGarde. Onigamiising: Seasons of an Ojibwe Year. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

[i] Linda LeGarde Grover is a member of the Bois Forte Band of Ojibwe and a professor emeritus of American Indian Studies at the University of Minnesota, Duluth. Her fiction, poetry, and creative nonfiction have received the Flannery O’Connor Award, the Northeastern Minnesota Book Award, the Janet Heidinger Kafka Prize, the Wordcraft Circle Award for Fiction, and the Minnesota Book Award.