I love the time between the winter Solstice and New Year’s – a time of suspended animation, a reprieve from the demands of daily life, a respite from the woes of the world, from needing to pay attention to the time of day and tasks that need to be accomplished. A whole week with nothing scheduled on the calendar. Simply presence. It is a liminal time — the threshold between the old year and the new – a time when we pause and reflect on the year past and our hopes for the year to come. It is a moment of what the Greeks called Kairos time, as opposed to Chronos time, by which we measure most of our lives -- in seconds, minutes, hours, days, and years.

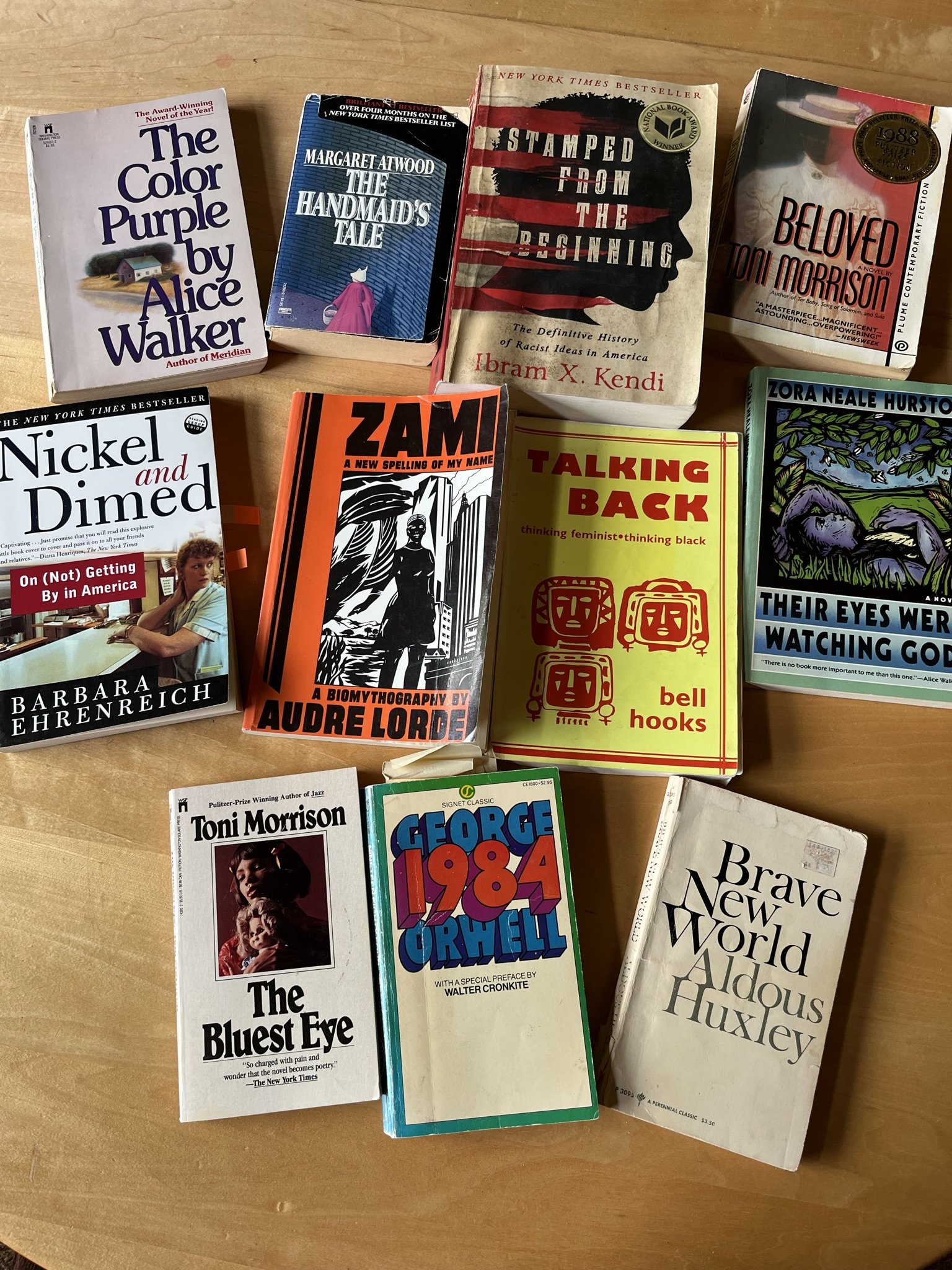

In the years I spent in academia, my time was governed by institutional structures of classes, meetings, due dates, and deadlines -- a Chronos time that often forced me to live in the future rather than the present. Course scheduling needed to happen far in advance. Book orders for the next semester needed to be placed mid-way through the previous one. Course syllabi planned students’ readings and assignments for the next several months ahead. Learning was to occur in specified blocks of times, which always struck me as such a bizarre way to teach and learn, when we’d have to break off discussion and deep learning simply because the hour was up.

One of the benefits of retirement is the ability to step off that particular treadmill. Nevertheless, most of the world lives on Chronos time. It is useful, allowing us to make appointments, find times to meet with friends, know when to put the trash out, pay bills, attend events and gatherings. But chronicity of time seems to be increasing. Get-togethers with friends no longer happen spontaneously. Instead, everyone gets out their planners to search for a mutually open spot. Even phone calls are scheduled now – texting first to see when someone might be free to talk.

Childhood has also changed that way. Other than school and being home in time for dinner, as children our days simply flowed from one activity to another, especially in the carefree days of summer. Now children’s lives are scheduled with after-school lessons and activities and camps. I remember distinctly the day my son told me that his life was too scheduled and he needed to drop some of his after-school activities. At seven! I’m grateful he knew he needed the time we all need simply to be, to create, to imagine, to play, to rest.

Chronos time vanishes in the wake of birth and death. The day my mother died I entered the space of grief time where my world stopped while the rest of the world went on. How strange it seemed that other people went about their daily lives as if nothing significant had happened, if it were just an ordinary day. It was as if I’d stepped off the space/time continuum and was watching life on earth from afar. The same was true on the day my son was born, where my world closed in to only this time, this place, this love, with no cognizance of any life beyond this moment. I’ve been able to create those spaces as well, on solo retreats where the days flow into each other and for a few days I am removed from the world, beholden to no clock and no one (except my dog). Snow days – those unexpected gifts from the snow goddesses where traffic stops; schools, stores, and workplaces close; events are cancelled -- grant us time simply for play – board games, sledding, building snowmen, playing fox and geese, and for hygge – the Scandinavian word that captures the essence of the coziness and conviviality of gathering under comforters, reading by the fire, and drinking hot cocoa while watching the snowflakes dance outside. It seems wrong that since schools learned how to rely on remote learning during the pandemic snow days have become “remote learning days” instead. We need those unexpected gifts of time and space occasionally to grace our lives. As ecotheologian Mary DeJong has said, “Chronos time is needed to survive. Kairos time is needed to thrive.”

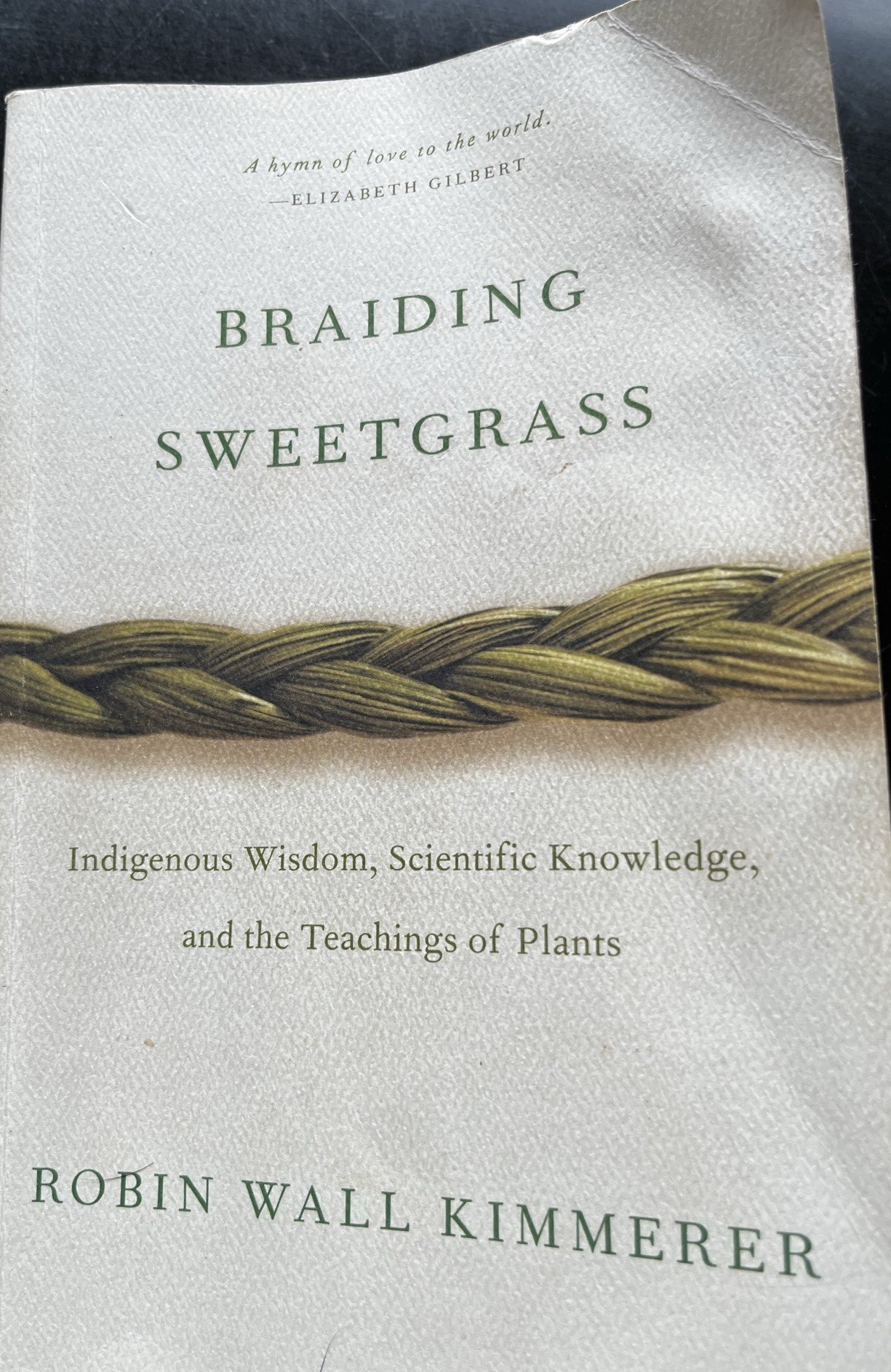

We don’t need to wait for life and the weather to grant us Kairos time. We can choose to make it a regular practice. We know it as “sabbath.” As practiced in Judaism, the weekly practice of Sabbath -- from sundown on Friday to sundown on Saturday -- is a time set aside from work, travel, devices, and screens. Minister Wayne Muller, author of my favorite book on Sabbath, writes, “In Sabbath time we remember to celebrate what is beautiful and sacred; we light candles, sing songs, tell stories, eat, nap, and make love. It is a time to let our work, our lands, our animals lie fallow, to be nourished and refreshed” (7). Whether a day, a week, or a few moments at the beginning and end of the day, we can commit to setting aside Chronos time and its demands to enter Kairos time, fully present to the present moment.

As I take time away from the news of continued death and destruction of war in Ukraine and Gaza, tensions in the Red Sea, mass shootings, the impending 2024 election -- I know my ability to insulate myself from that world for a time is a privilege not granted to those who are living in the midst of it. Yet I also know that taking regular sabbath time is an antidote to violence. As Muller writes, “Sabbath time . . . can invite a healing of this violence. . . . When we act from, a place of deep rest, we are more capable of cultivating what the Buddhists would call right understanding, right action, and right effort. . . .Once people feel nourished and refreshed, they cannot help but be kind; just so, the world aches for the generosity of well-rested people” (5,7, 11).

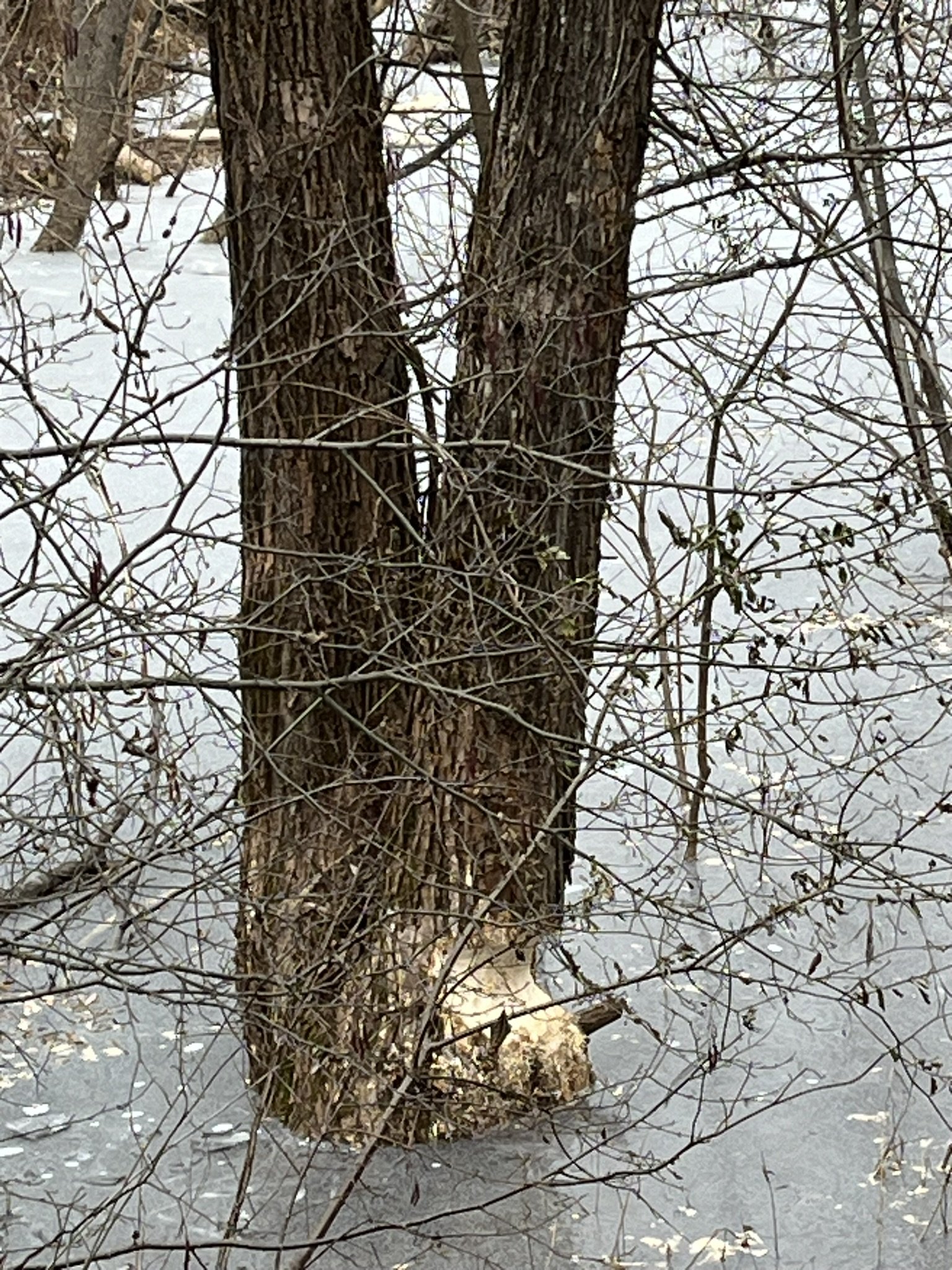

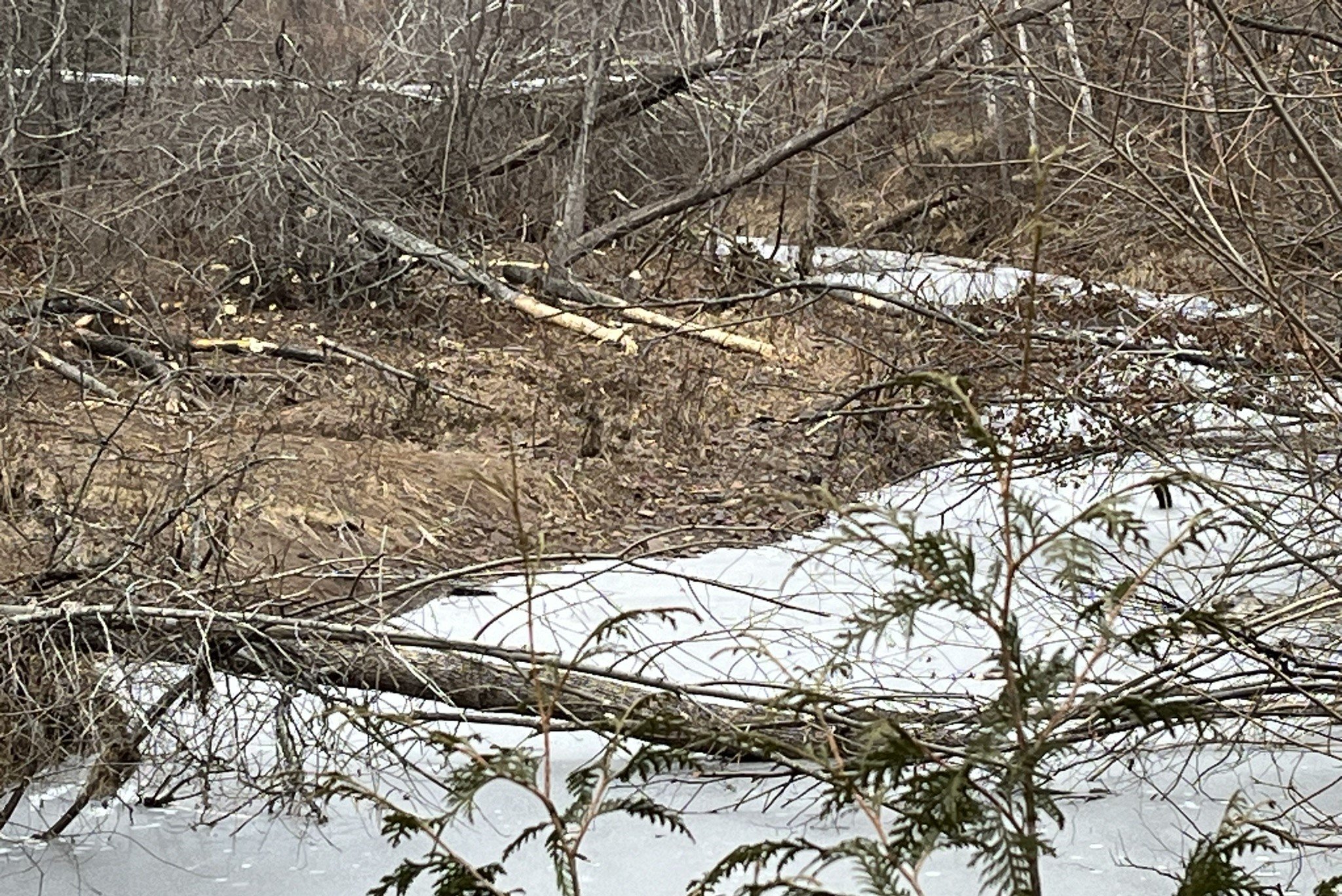

The forecast is looking hopeful for an upcoming snow day. Oh that we could grant the world a year of snow days, where all the world could, in the words of the mystic Rumi, “Come out of the circle of time, and into the circle of love.”

Sources

DeJong, Mary. “Wild Autumn.” Waymarkers.

Muller, Wayne. 1999. Sabbath: Restoring the Sacred Rhythm of Rest. New York: Bantam.